JEEVES ... will be away for two weeks.

↧

↧

Coming Soon : Chris Steele-Perkins’ book "A Place In The Country".

Holkham Hall: a modern-day Downton

There’s a butler, a gamekeeper, a cook – and everyone swears it’s nothing like Downton Abbey. But what keeps a country estate alive in 2014? Magnum photographer Chris Steele-Perkins spends a year at Holkham Hall in Norfolk

Words: Photographs:

The Guardian, Friday 17 October 2014 / http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/oct/17/holkham-hall-norfolk-a-modern-day-downton-abbey?CMP=fb_gu

Pass between the gatehouses, down the sweeping drive towards Holkham Hall, and you enter a time warp. Fallow deer cluster scenically under broad oaks, geese honk as they rise from the silver lake. It could almost be 1764, the year the grand house was completed, shortly after the death of Thomas Coke, the first Earl of Leicester.

The estate is now run by Viscount Thomas Coke, the son of the seventh Earl of Leicester. Photographs by Chris Steele-Perkins, who documented the 25,000-acre estate in Norfolk

Holkham has diversified into 48 different businesses serving both aristocratic and popular tastes, from a boutique hotel to a caravan park and 300 houses, mostly let to local people. There are 200 full-time and 150 seasonal staff – including six gamekeepers and a butler, but also a conservation manager and education officer, too. Holkham’s walled estate is open to the public, hosting concerts and festivals. Each year, more than half a million people visit Holkham’s beach, which is a national nature reserve and, unusually, is entrusted to the privately owned estate rather than the government’s wildlife body Natural England.

The Cokes (pronounced “Cook”) are more generous over public access than most great estates, but they are wary of the media. David Horton-Fawkes, estates director, admits they were nervous about giving access to Steele-Perkins, a member of the Magnum collective who has documented poverty around Britain

In fact, Steele-Perkins found a bustling, busy estate which he likens to “a well-run ship”. “I started to think of the estate in nautical terms,” he notes in an introduction to his book of these photographs. “A long time ago I had spent a week on the aircraft carrier HMS Invincible where the crew was organised into myriad teams, but worked together as an organic whole when needed. Holkham is similar: building maintenance, farming, forestry, gamekeeping, with their officers and their petty officers and their ratings, in effect.”

For much of the 20th century, country piles such as Holkham were an endangered species. Prohibitive death duties between the wars caused the break-up of many great estates, which were sold for development, handed over to the National Trust or, incredibly, demolished. Holkham held 42,000 acres in the late 1940s when the fourth earl, another Thomas Coke, tried to pass it to the National Trust. That deal never happened and the Cokes were down to their last 25,000 acres in 1973 when Edward, father of the current incumbent, began running the estate. “When he took over in 1973, every facet was losing money,” says Viscount Coke, 49, who lives in part of the hall with his wife Polly and their four children.

When Coke returned to his family seat aged 28, after Eton , university and the army, he remembers his father looking at him and saying, “What are you doing here?” The seventh earl (who is still alive) managed a mix of farming, forestry and shooting, with a few tourists visiting the house, and he didn’t need any help. So the young heir began by looking after a large caravan park – “We’d prefer to say holiday park,” Coke says, “we’ve invested a lot on landscaping and making it nice” – which had returned to the estate after the local council’s lease ended.

Twenty years ago, 75% of Holkham’s turnover came from the land. Now, tourism and leisure make up 55% of turnover; farming and property rentals are only 40%. Coke was given full control of the estate seven years ago and appointed Horton-Fawkes two years ago. “For a landowner, I’m not bad at this customer service sort of thing, but David introduced me to a whole new level,” Coke says. “I don’t think I’ve uttered the word ‘punter’ for the last few years – I have to say things like ‘guest’.” Such openness has been rewarded: Coke is surprised that his walled garden is now tended by 23 volunteers. “I always thought people would happily volunteer for the National Trust, but to volunteer for Little Lord Fauntleroy living in a big house – it’s amazing we’ve got to that position.”

In many ways, the estate resembles any other modern corporation. Coke has introduced board meetings and non-executive directors, “people with experience from outside”. Senior staff recently visited Volvo’s HQ in Gothenburg to see how they did business, and they already have some unusual incentives in place: if an employee doesn’t perform a task on time, they must bake a cake. Coke is not exempt although, he admits, when called upon he “made two loaves of bread in the breadmaker”.

Coke and his wife have a private staff of three, compared with 50 in the Downton era, though this does include a butler. When Coke took over the estate, he says, “I thought, ‘Dad had a butler, I’m not going to have one’ – but it’s such a big house.” The butler, Steele-Perkins notes, is “quite young and nothing like the butler of fiction”. He wears full butler attire only for formal occasions, and Steele-Perkins spent time with the staff while they prepared for one such event: a black-tie dinner for 24 people. “Laying the table, lining up the glasses, took hours.”

Steele-Perkins was surprised to find that even among themselves, staff refer to their bosses as “Lord” and “Lady”. Horton-Fawkes says that Tom and Polly “lost a lot of sleep” over this. “They are very approachable, and didn’t want that deferential relationship,” he says. Nevertheless, they decided to retain a traditional formality to “reinforce the boundary between work and home”.

As for the staff, it seems that old habits die hard. “I quite like saying ‘Lord Coke’, that formality seems right for the estate,” says Sarah Henderson, Holkham’s conservation manager. Kevan McCaig, the head gamekeeper, who was previously employed by the royal family at Sandringham , says he is “more comfortable” calling his boss Lord Coke. “In different places I’ve worked I’ve never called anybody by their first name,” he says.

McCaig lives in a cottage in the grounds. Only one member of staff lives in the hall itself: the head of security. But while he was working there, Steele-Perkins was able to stay in the house. “It could be quite spooky,” he says, “coming back there at night, torch in hand, after dining at one of the pubs that Holkham owns, footsteps echoing down stone paved corridors above the haunted cellars, a whisper of wind around the windows…” Over the course of the year, as the family got to know him better, he graduated from the butler’s quarters to the guest bedrooms. He remembers one night staying in a bedroom with Italian Renaissance paintings on the wall - a room which, he recalls, “had a footprint bigger than that of my whole house in London

• Chris Steele-Perkins’ book A Place In The Country, from which these photographs are taken, is published by Dewi Lewis next month, priced £25.

Steele-Perkins was born in Rangoon, Burma in 1947 to a British father and a Burmese mother; but his father left his mother and took the boy to England at the age of two. He went to Christ's Hospital and for one year studied chemistry at the University of York before leaving for a stay in Canada. Returning to Britain, he joined the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, where he served as photographer and picture editor for a student magazine. After graduating in psychology in 1970 he started to work as a freelance photographer, specializing in the theatre, while he also lectured in psychology.

By 1971, Steele-Perkins had moved to London and become a full-time photographer, with particular interest in urban issues, including poverty. He went to Bangladesh in 1973 to take photographs for relief organizations; some of this work was exhibited in 1974 at the Camerawork Gallery (London). In 1973–74 he taught photography at the Stanhope Institute and the North East London Polytechnic.

In 1975, Steele-Perkins joined the Exit Photography Group with the photographers Nicholas Battye and Paul Trevor, and there continued his examination of urban problems: Exit's earlier booklet Down Wapping had led to a commission by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation to increase the scale of their work, and in six years they produced 30,000 photographs as well as many hours of taped interviews. This led to the 1982 book Survival Programmes. Steele-Perkins' work included depiction from 1975 to 1977 of street festivals, and prints from London Street Festivals were bought by the British Council and exhibited with Homer Sykes' Once a Year and Patrick Ward's Wish You Were Here; Steele-Perkins' depiction of Notting Hill has been described as being in the vein of Tony Ray-Jones.

Steele-Perkins became an associate of the French agency Viva in 1976, and three years after this, he published his first book, The Teds, an examination of teddy boys that is now considered a classic of documentary and even fashion photography. He curated photographs for the Arts Council collection, and co-edited a collection of these, About 70 Photographs.

In 1977 Steele-Perkins had made a short detour into "conceptual" photography, working with the photographer Mark Edwards to collect images from the ends of rolls of films taken by others, exposures taken in a rush merely in order to finish the roll. Forty were exhibited in "Film Ends".

Work documenting poverty in Britain took Steele-Perkins to Belfast, which he found to be poorer than Glasgow, London, Middlesbrough, or Newcastle, as well as experiencing "a low-intensity war".

He stayed in the Catholic Lower Falls area, first squatting and then staying in the flat of a man he met in Belfast. His photographs of Northern Ireland appeared in a 1981 book written by Wieland Giebel. Thirty years later, he would return to the area to find that its residents had new problems and fears; the later photographs appear within Magnum Ireland.

He stayed in the Catholic Lower Falls area, first squatting and then staying in the flat of a man he met in Belfast. His photographs of Northern Ireland appeared in a 1981 book written by Wieland Giebel. Thirty years later, he would return to the area to find that its residents had new problems and fears; the later photographs appear within Magnum Ireland.

Steele-Perkins photographed wars and disasters in the third world, leaving Viva in 1979 to join Magnum Photos as a nominee (on encouragement by Josef Koudelka), and becoming an associate member in 1981 and a full member in 1983. He continued to work in Britain, taking photographs published as The Pleasure Principle, an examination (in colour) of life in Britain but also a reflection of himself. With Philip Marlow, he successfully pushed for the opening of a London office for Magnum; the proposal was approved in 1986.

Steele-Perkins made four trips to Afghanistan in the 1990s, sometimes staying with the Taliban, the majority of whom "were just ordinary guys" who treated him courteously. Together with James Nachtwey and others, he was also fired on, prompting him to reconsider his priorities: in addition to the danger of the front line:

. . . you never get good pictures out of it. I've yet to see a decent front-line war picture. All the strong stuff is a bit further back, where the emotions are.

A book of his black and white images, Afghanistan, was published first in French, and later in English and in Japanese. The review in the Spectator read in part:

These astonishingly beautiful photographs are more moving than can be described; they hardly ever dwell on physical brutalities, but on the bleak rubble and desert of the country, punctuated by inexplicable moments of formal beauty, even pastoral bliss . . . the grandeur of the images comes from Steele-Perkins never neglecting the human, the individual face in the great crowd of history.

—Philip Hensher

The book and the travelling exhibition of photographs were also reviewed favorably in the Guardian, Observer, Library Journal, and London Evening Standard.

Steele-Perkins served as the President of Magnum from 1995 to 1998. One of the annual meetings over which he presided was that of 1996, to which Russell Miller was given unprecedented access as an outsider and which Miller has described in some detail.

With his second wife the presenter and writer Miyako Yamada (山田美也子), whom he married in 1999, Steele-Perkins has spent much time in Japan, publishing two books of photographs: Fuji, a collection of views and glimpses of the mountain inspired by Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji; and Tokyo Love Hello, scenes of life in the city. Between these two books he also published a personal visual diary of the year 2001, Echoes.

Work in South Korea included a contribution to a Hayward Gallery touring exhibition of photographs of contemporary slavery, "Documenting Disposable People", in which Steele-Perkins interviewed and made black-and-white photographs of Korean "comfort women". "Their eyes were really important to me: I wanted them to look at you, and for you to look at them", he wrote. "They're not going to be around that much longer, and it was important to give this show a history." The photographs were published within Documenting Disposable People: Contemporary Global Slavery.

Steele-Perkins returned to England for a project by the Side Gallery on Durham's closed coalfields (exhibited within "Coalfield Stories"); after this work ended, he stayed on to work on a depiction (in black and white) of life in the north-east of England, published as Northern Exposures.

In 2008 Steele-Perkins won an Arts Council England grant for "Carers: The Hidden Face of Britain", a project to interview those caring for their relatives at home, and to photograph the relationships. Some of this work has appeared in The Guardian, and also in his book England, My England, a compilation of four decades of his photography that combines photographs taken for publication with much more personal work: he does not see himself as having a separate personality when at home. "By turns gritty and evocative," wrote a reviewer in The Guardian, "it is a book one imagines that Orwell would have liked very much."

Steele-Perkins has two sons, Cedric, born 16 November 1990, and Cameron, born 18 June 1992. With his marriage to Miyako Yamada he has a stepson, Daisuke and a granddaughter, Momoe.

Holkham Hall is an 18th-century country house located adjacent to the village of Holkham, Norfolk, England. The house was constructed in the Palladian style for Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester (fifth creation) by the architect William Kent, aided by the architect and aristocrat Lord Burlington.

Holkham Hall is one of England's finest examples of the Palladian revival style of architecture, and severity of its design is closer to Palladio's ideals than many of the other numerous Palladian style houses of the period. The Holkham estate, formerly known as Neals, had been purchased in 1609 by Sir Edward Coke, the founder of his family fortune. It is the ancestral home of the Coke family, the Earls of Leicester of Holkham.

The interior of the hall is opulently but, by the standards of the day, simply decorated and furnished. Ornament is used with such restraint that it was possible to decorate both private and state rooms in the same style, without oppressing the former. The principal entrance is through the "Marble" Hall, which leads to the piano nobile, or the first floor, and state rooms. The most impressive of these rooms is the saloon, which has walls lined with red velvet. Each of the major state rooms is symmetrical in its layout and design; in some rooms, false doors are necessary to fully achieve this balanced effect.

Holkham was built by first Earl of Leicester, Thomas Coke, who was born in 1697. A cultivated and wealthy man, Coke made the Grand Tour in his youth and was away from England for six years between 1712 and 1718. It is likely he met both Burlington—the aristocratic architect at the forefront of the Palladian revival movement in England—and William Kent in Italy in 1715, and that in the home of Palladianism the idea of the mansion at Holkham was conceived. Coke returned to England, not only with a newly acquired library, but also an art and sculpture collection with which to furnish his planned new mansion. However, after his return, he lived a feckless life, preoccupying himself with drinking, gambling and hunting, and being a leading supporter of cockfighting. He made a disastrous investment in the South Sea Company and when the South Sea Bubble burst in 1720, the resultant losses delayed the building of Coke's planned new country estate for over ten years. Coke, who had been made Earl of Leicester in 1744, died in 1759—five years before the completion of Holkham—having never fully recovered his financial losses. Thomas's wife, Lady Margaret Tufton, Countess of Leicester (1700–1775), would oversee the finishing and furnishing of the House.

Although Colen Campbell was employed by Thomas Coke in the early 1720s, the oldest existing working and construction plans for Holkham were drawn by Matthew Brettingham, under the supervision of Thomas Coke, in 1726. These followed the guidelines and ideals for the house as defined by Kent and Burlington. The Palladian revival style chosen was at this time making its return in England. The style made a brief appearance in England before the Civil War, when it was introduced by Inigo Jones. However, following the Restoration it was replaced in popular favour by the Baroque style. The "Palladian revival", popular in the 18th century, was loosely based on the appearance of the works of the 16th-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio. However it did not, adhere to Palladio's strict rules of proportion. The style eventually evolved into what is generally referred to as Georgian, still popular in England today. It was the chosen style for numerous houses in both town and country, although Holkham is exceptional for both its severity of design and for being closer than most in its adherence to Palladio's ideals.

Although Thomas Coke oversaw the project, he delegated the on-site architectural duties to the local Norfolk architect Matthew Brettingham, who was employed as the on-site clerk of works. Brettingham was already the estate architect, and was in receipt of £50 a year (about 7,000 pounds per year in 2014 terms in return for "taking care of his Lordship's buildings". William Kent was mainly responsible for the interiors of the Southwest pavilion, or family wing block, particularly the Long Library. Kent produced a variety of alternative exteriors, suggesting a far richer decoration than Coke wanted. Brettingham described the building of Holkham as "the great work of [my life]", and when he published his "The Plans and Elevations of the late Earl of Leicester's House at Holkham", he immodestly described himself as sole architect, making no mention of Kent's involvement. However, in a later edition of the book, Brettingham's son admitted that "the general idea was first struck out by the Earls of Leicester and Burlington, assisted by Mr. William Kent".

In 1734, the first foundations were laid; however, building was to continue for thirty years, until the completion of the great house in 1764.

The Palladian style was admired by Whigs such as Thomas Coke, who sought to identify themselves with the Romans of antiquity. Kent was responsible for the external appearance of Holkham; he based his design on Palladio's unbuilt Villa Mocenigo,] as it appears in I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura, but with modifications.

The plans for Holkham were of a large central block of two floors only, containing on the piano nobile level a series of symmetrically balanced state rooms situated around two courtyards. No hint of these courtyards is given externally; they are intended for lighting rather than recreation or architectural value. This great central block is flanked by four smaller, rectangular blocks, or wings, and at each corners is linked to the main house not by long colonnades—as would have been the norm in Palladian architecture—but by short two-storey wings of only one bay.

The external appearance of Holkham can best be described as a huge Roman palace. However, as with most architectural designs, it is never quite that simple. Holkham is a Palladian house, and yet even by Palladian standards the external appearance is austere and devoid of ornamentation. This can almost certainly be traced to Coke himself. The on-site, supervising architect, Matthew Brettingham, related that Coke required and demanded "commodiousness", which can be interpreted as comfort. Hence rooms that were adequately lit by one window, had only one, as a second might have improved the external appearance but could have made a room cold or draughty. As a result the few windows on the piano nobile, although symmetrically placed and balanced, appear lost in a sea of brickwork; albeit these yellow bricks were cast as exact replicas of ancient Roman bricks expressly for Holkham. Above the windows of the piano nobile, where on a true Palladian structure the windows of a mezzanine would be, there is nothing. The reason for this is the double height of the state rooms on the piano nobile; however, not even a blind window, such as those often seen in Palladio's own work, is permitted to alleviate the severity of the facade. On the ground floor, the rusticated walls are pierced by small windows more reminiscent of a prison than a grand house. One architectural commentator, Nigel Nicolson, has described the house as appearing as functional as a Prussian riding school.

The principal, or South facade, is 344 feet (104.9 m) in length (from each of the flanking wings to the other), its austerity relieved on the piano nobile level only by a great six-columned portico. Each end of the central block is terminated by a slight projection, containing a Venetian window surmounted by a single storey square tower and capped roof, similar to those employed by Inigo Jones at Wilton House nearly a century earlier. A near identical portico was designed by Inigo Jones and Isaac de Caus for the Palladian front at Wilton, but this was never executed.

The flanking wings contain service and secondary rooms—the family wing to the south-west; the guest wing to the north-west; the chapel wing to the south-east; and the kitchen wing to the north-east. Each wing's external appearance is identical: three bays, each separated from the other by a narrow recess in the elevation. Each bay is surmounted by an unadorned pediment. The composition of stone, recesses, varying pediments and chimneys of the four blocks is almost reminiscent of the English Baroque style in favour ten years earlier, employed at Seaton Delaval Hall by Sir John Vanbrugh. One of these wings, as at the later Kedleston Hall, was a self-contained country house to accommodate the family when the state rooms and central block were not in use.

The one storey porch at the main north entrance was designed in the 1850s by Samuel Sanders Teulon, although stylistically it is indistinguishable from the 18th century building.

Inside the house, the Palladian form reaches a height and grandeur seldom seen in any other house in England. It has, in fact, been described as "The finest Palladian interior in England."[20] The grandeur of the interior is obtained with an absence of excessive ornament, and reflects Kent's career-long taste for "the eloquence of a plain surface". Work on the interiors ran from 1739 to 1773. The first habitable rooms were in the family wing and were in use from 1740, the Long Library being the first major interior completed in 1741. Among the last to be completed and entirely under Lady Leicester's supervision is the Chapel with its alabaster reredos. The house is entered through the "Marble" Hall (the chief building fabric is in fact Derbyshire alabaster), modelled by Kent on a Roman basilica. The room is over 50 feet (15 m) from floor to ceiling and is dominated by the broad white marble flight of steps leading to the surrounding gallery, or peristyle: here alabaster Ionic columns support the coffered, gilded ceiling, copied from a design by Inigo Jones, inspired by the Pantheon in Rome. The fluted columns are thought to be replicas of those in the Temple of Fortuna Virilis, also in Rome. Around the hall are statues in niches; these are predominantly plaster copies of classical deities.

The hall's flight of steps lead to the piano nobile and state rooms. The grandest, the saloon, is situated immediately behind the great portico, with its walls lined with patterned red Genoa velvet and a coffered, gilded ceiling. In this room hangs Rubens's Return from Egypt. On his Grand Tour, the Earl acquired a collection of Roman copies of Greek and Roman sculpture which is contained in the massive "Statue Gallery", which runs the full length of the house north to south. The North Dining Room, a cube room of 27 feet (8.2 m) contains an Axminster carpet that perfectly mirrors the pattern of the ceiling above. A bust of Aelius Verus, set in a niche in the wall of this room, was found during the restoration at Nettuno. A classical apse gives the room an almost temple air. The apse in fact, contains concealed access to the labyrinth of corridors and narrow stairs that lead to the distant kitchens and service areas of the house. Each corner of the east side of the principal block contains a square salon lit by a huge Venetian window, one of them—the Landscape Room—hung with paintings by Claude Lorrain and Gaspar Poussin. All of the major state rooms have symmetrical walls, even where this involves matching real with false doors. The major rooms also have elaborate white and multi-coloured marble fireplaces, most with carvings and sculpture, mainly the work of Thomas Carter, though Joseph Pickford carved the fireplace in the Statue Gallery. Much of the furniture in the state rooms was also designed by William Kent, in a stately classicising baroque manner.

So restrained is the interior decoration of the state rooms, or in the words of James Lees-Milne, "chaste", that the smaller, more intimate rooms in the family's private south-west wing were decorated in similar vein, without being overpowering. The long library running the full length of the wing still contains the collection of books acquired by Thomas Coke on his Grand Tour through Italy, where he saw for the first time the Palladian villas which were to inspire Holkham.

The Green State bedroom is the principal bedroom; it is decorated with paintings and tapestries, including works by Paul Saunders and George Smith Bradshaw. It is said that when Queen Mary visited, Gavin Hamilton's "lewd" depiction of Jupiter Caressing Juno "was considered unsuitable for that lady's eyes and was banished to the attics"

↧

"HUSKY"

|

Husky was founded in 1965 by retired American airman Steve Gulyas and his wife Edna/ - Husky Ltd in Tostock, Husky was sold in 90’s to Described in http://shoptrotter.com/brands/husky-1965/: “Husky is an Italian clothing brand, founded in 1965, which gained instant popularity with its Husky jacket, designer by a retired American airman Steve Gulyas and his wife Edna. Comfortable and weather-proof Husky jacket soon became a favourite hunting outfit for Queen Elizabeth and other members of the english Royal Family. Nowadays Husky offers much wider choice of comfy and weather-proof clothing, perfect for a hunting or a fishing trip.” |

↧

INTERMEZZO ... REMAINS OF THE DAY ...

↧

The urgent need of slowing down in the way we experience and approach art in a Museum.

The Art of Slowing Down in a Museum

OCTOBER 9, 2014 / New York Times / http://mobile.nytimes.com/2014/10/12/travel/the-art-of-slowing-down-in-a-museum.html?referrer=&_r=0

Stephanie Rosenbloom

Ah, the Louvre. It’s sublime, it’s historic, it’s … overwhelming.

Upon entering any vast art museum — the Hermitage, the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art — the typical traveler grabs a map and spends the next two hours darting from one masterpiece to the next, battling crowds, exhaustion and hunger (yet never failing to take selfies with boldface names like Mona Lisa).

What if we slowed down? What if we spent time with the painting that draws us in instead of the painting we think we’re supposed to see?

Most people want to enjoy a museum, not conquer it. Yet the average visitor spends 15 to 30 seconds in front of a work of art, according to museum researchers. And the breathless pace of life in our Instagram age conspires to make that feel normal. But what’s a traveler with a long bucket list to do? Blow off the Venus de Milo to linger over a less popular lady like Diana of Versailles?

“When you go to the library,” said

James O. Pawelski, the director of education for the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, “you don’t walk along the shelves looking at the spines of the books and on your way out tweet to your friends, ‘I read 100 books today!'” Yet that’s essentially how many people experience a museum. “They see as much of art as you see spines on books,” said Professor Pawelski, who studies connections between positive psychology and the humanities. “You can’t really see a painting as you’re walking by it.”

James O. Pawelski, the director of education for the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, “you don’t walk along the shelves looking at the spines of the books and on your way out tweet to your friends, ‘I read 100 books today!'” Yet that’s essentially how many people experience a museum. “They see as much of art as you see spines on books,” said Professor Pawelski, who studies connections between positive psychology and the humanities. “You can’t really see a painting as you’re walking by it.”

There is no right way to experience a museum, of course. Some travelers enjoy touring at a clip or snapping photos of timeless masterpieces. But psychologists and philosophers such as Professor Pawelski say that if you do choose to slow down — to find a piece of art that speaks to you and observe it for minutes rather than seconds — you are more likely to connect with the art, the person with whom you’re touring the galleries, maybe even yourself, he said. Why, you just might emerge feeling refreshed and inspired rather than depleted.

To demonstrate this, Professor Pawelski takes his students to the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia

Julie Haizlip wasn’t so sure. A scientist and self-described left-brain thinker, Dr. Haizlip is a clinical professor at the School of Nursing and the Division of Pediatric Critical Care at the University of Virginia

“I have to admit I was a bit skeptical,” said Dr. Haizlip, who had never spent 20 minutes looking at a work of art and prefers Keith Haring, Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock to Matisse, Rousseau and Picasso, whose works adorn the Barnes.

Any museumgoer can do what Professor Pawelski asks students such as Dr. Haizlip to do: Pick a wing and begin by wandering for a while, mentally noting which works are appealing or stand out. Then return to one that beckons. For instance, if you have an hour he suggests wandering for 30 minutes, and then spending the next half-hour with a single compelling painting. Choose what resonates with you, not what’s most famous (unless the latter strikes a chord).

Indeed, a number of museums now offer “slow art” tours or days that encourage visitors to take their time. Rather than check master works off a list as if on a scavenger hunt, Sandra Jackson-Dumont, who oversees the education programs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Initially, nothing in the Barnes grabbed Dr. Haizlip. Then she spotted a beautiful, melancholy woman with red hair like her own. It was Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting of a prostitute, “AMontrouge” — Rosa La Rouge.

“I was trying to figure out why she had such a severe look on her face,” said Dr. Haizlip. As the minutes passed, Dr. Haizlip found herself mentally writing the woman’s story, imagining that she felt trapped and unhappy — yet determined. Over her shoulder, Toulouse-Lautrec had painted a window. “There’s an escape,” Dr. Haizlip thought. “You just have to turn around and see it.”

“I was actually projecting a lot of me and what was going on in my life at that moment into that painting,” she continued. “It ended up being a moment of self-discovery.” Trained as a pediatric intensive-care specialist, Dr. Haizlip was looking for some kind of change but wasn’t sure what. Three months after her encounter with the painting, she changed her practice, accepting a teaching position at the University of Virginia ’s School of Nursing

Professor Pawelski said it’s still a mystery why viewing art in this deliberately contemplative manner can increase well-being or what he calls flourishing. That’s what his research is trying to uncover. He theorized, however, that there is a connection to research on meditation and its beneficial biological effects. In a museum, though, you’re not just focusing on your breath, he said. “You’re focusing on the work of art.”

Previous research, including a study led by Stephen Kaplan at the University of Michigan

Ms. Jackson-Dumont, who has also worked at the Seattle Art Museum, the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Whitney Museum of American Art, said travelers should feel empowered to “curate” their own experience. Say, for example, you do not like hearing chatter when you look at art. Ms. Jackson-Dumont suggests making your own soundtrack at home and taking headphones to the museum so that you can stroll the galleries accompanied by music. “I think people feel they have to behave a certain way in a museum,” she said. “You can actually be you.”

To that end, many museums are encouraging visitors to take selfies with the art and post them on social media. (In case you missed it, Jan. 22 was worldwide "MuseumSelfie" day with visitors sharing their best work on Twitter using an eponymous hashtag.) Selfie-takers often pose like the subject of the painting or sculpture behind them. To some visitors that seems crass, distracting or antithetical to contemplation. But surprisingly, Ms. Jackson-Dumont has observed that when museumgoers strike an art-inspired pose, it not only creates camaraderie among onlookers but it gives the selfie-takers a new appreciation for the art. In fact, taking on the pose of a sculpture, for example, is something the Met does with visitors who are blind or partially sighted because “feeling the pose” can allow them to better understand the work.

There will always be certain paintings or monuments that travelers feel they must see, regardless of crowds or lack of time. To winnow the list, Ms. Jackson-Dumont suggests asking yourself: What are the things that, if I do not see them, will leave me feeling as if I didn’t have a New York

The next time you step into a vast treasure trove of art and history, allow yourself to be carried away by your interests and instincts. You never know where they might lead you. Before leaving the Barnes on that March afternoon, Dr. Haizlip had another unexpected moment: She bought a print of the haunting Toulouse-Lautrec woman.

“I felt like she had more to tell me,” she said.

PARIS

Stephanie Rosenbloom is The Getaway columnist for the Travel section. Previously, she was a New York Times staff reporter for Style where she wrote about American social trends including fashion, technology and love in a digital age. Prior to that she was the retailing reporter for Business Day, where she wrote about money and happiness and covered companies like Walmart, Saks and Macy’s during the financial crisis of 2008.

She appears regularly in New York Times videos and is a featured writer in “The New York Times, 36 Hours: 150 Weekends in the USA & Canada ” (Taschen, 2011) and “The New York Times Practical Guide to Practically Everything” (St. Martin ’s Press, 2006)

At Louvre, Many Stop to Snap but Few Stay to Focus

By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN

Published: August 2, 2009 / http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/03/arts/design/03abroad.html

At the Louvre the other day, in the Pavillon des Sessions, two young women in flowered dresses meandered through the gallery. They paused and circled around a few sculptures. They took their time. They looked slowly.

The pavilion puts some 100 immaculate objects from outside Europe on permanent view in a ground floor suite of cool, silent galleries at one end of the museum. Feathered masks from Alaska , ancient bowls from the Philippines

The young women were unusual for stopping. Most of the museum’s visitors passed through the gallery oblivious.

A few game tourists glanced vainly in guidebooks or hopefully at wall labels, as if learning that one or another of these sculptures came from Papua New Guinea or Hawaii or the Archipelago of Santa Cruz, or that a work was three centuries old or maybe four might help them see what was, plain as day, just before them.

Almost nobody, over the course of that hour or two, paused before any object for as long as a full minute. Only a 17th-century wood sculpture of a copulating couple, from San Cristobal in the Solomon Islands, placed near an exit, caused several tourists to point, smile and snap a photo, but without really breaking stride.

Visiting museums has always been about self-improvement. Partly we seem to go to them to find something we already recognize, something that gives us our bearings: think of the scrum of tourists invariably gathered around the Mona Lisa. At one time a highly educated Westerner read perhaps 100 books, all of them closely. Today we read hundreds of books, or maybe none, but rarely any with the same intensity. Travelers who took the Grand Tour across Europe during the 18th century spent months and years learning languages, meeting politicians, philosophers and artists and bore sketchbooks in which to draw and paint — to record their memories and help them see better.

Cameras replaced sketching by the last century; convenience trumped engagement, the viewfinder afforded emotional distance and many people no longer felt the same urgency to look. It became possible to imagine that because a reproduction of an image was safely squirreled away in a camera or cell phone, or because it was eternally available on the Web, dawdling before an original was a waste of time, especially with so much ground to cover.

We could dream about covering lots of ground thanks to expanding collections and faster means of transportation. At the same time, the canon of art that provided guideposts to tell people where to go and what to look at was gradually dismantled. A core of shared values yielded to an equality among visual materials. This was good and necessary, up to a point. Millions of images came to compete for our attention. Liberated by a proliferation, Western culture was also set adrift in an ocean of passing stimulation, with no anchors to secure it.

So tourists now wander through museums, seeking to fulfill their lifetime’s art history requirement in a day, wondering whether it may now be the quantity of material they pass by rather than the quality of concentration they bring to what few things they choose to focus upon that determines whether they have “done” the Louvre. It’s self-improvement on the fly.

The art historian T. J. Clark, who during the 1970s and ’80s pioneered a kind of analysis that rejected old-school connoisseurship in favor of art in the context of social and political affairs, has lately written a book about devoting several months of his time to looking intently at two paintings by Poussin. Slow looking, like slow cooking, may yet become the new radical chic.

Until then we grapple with our impatience and cultural cornucopia. Recently, I bought a couple of sketchbooks to draw with my 10-year-old in St. Peter’s and elsewhere around Rome, just for the fun of it, not because we’re any good, but to help us look more slowly and carefully at what we found. Crowds occasionally gathered around us as if we were doing something totally strange and novel, as opposed to something normal, which sketching used to be. I almost hesitate to mention our sketching. It seems pretentious and old-fogeyish in a cultural moment when we can too easily feel uncomfortable and almost ashamed just to look hard.

Artists fortunately remind us that there’s in fact no single, correct way to look at any work of art, save for with an open mind and patience. If you have ever gone to a museum with a good artist you probably discovered that they don’t worry so much about what art history books or wall labels tell them is right or wrong, because they’re selfish consumers, freed to look by their own interests.

Back to those two young women at the Louvre: aspiring artists or merely curious, they didn’t plant themselves forever in front of the sculptures but they stopped just long enough to laugh and cluck and stare, and they skipped the wall labels until afterward.

They looked, in other words. And they seemed to have a very good time.

Leaving, they caught sight of a sculptured effigy from Papua New Guinea

They thought for a moment. “Nyah-nyah,” they said in unison. Then blew him a raspberry.

↧

↧

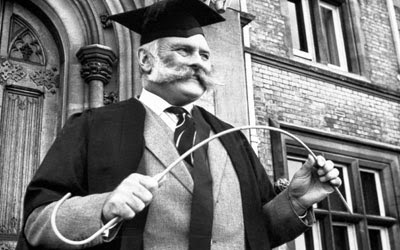

Remembering the great Jimmy Edwards . Watch the VÍDEO bellow /Whacko! [1960]/ Hold on! It takes some seconds to start ...

Jimmy Edwards, DFC (23 March 1920 – 7 July 1988) was an English comedic script writer and comedy actor on both radio and television, best known as Pa Glum in Take It From Here and as the headmaster "Professor" James Edwards in Whack-O!

Edwards was born James Keith O'Neill Edwards in Barnes, London St Paul 's Cathedral School , at King's College School in Wimbledon, London , and later at St John's College , Cambridge

He served in the Royal Air Force during World War II, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross. His Dakota was shot down at Arnhem

Edwards was a feature of London theatre in the immediate post-war years, debuting at London

Graduating to television, he appeared in Whack-O, also written by Muir and Norden, and the radio panel game Does the Team Think?, a series which Edwards also created. In 1960 a film version of Whack-O called Bottoms Up was made, written by Muir and Norden. On TV he also appeared in The Seven Faces of Jim, Six More Faces of Jim, and More Faces of Jim, in guest slots in Make Room for Daddy and Sykes, in Bold As Brass, I Object, John Jorrocks Esq, The Auction Game, Jokers Wild, Sir Yellow, Doctor in the House, Charley's Aunt and Oh! Sir James! (which he also wrote).

He was the subject of This Is Your Life in 1958 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at the BBC's Piccadilly 1 Studio.

Edwards also starred in The Fossett Saga in 1969 as James Fossett, an ambitious Victorian writer of penny dreadfuls, with Sam Kydd playing Herbert Quince, his unpaid manservant, and June Whitfield playing music-hall singer Millie Goswick. This was shown on Fridays at 8:30 pm on LWT; David Freeman was the creator.

In December 1958, Jimmy Edwards played the King in Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella at the London Coliseum with Kenneth Williams, Tommy Steele, Yana and Betty Marsden. In April 1966, Edwards performed at the last night of Melbourne Britain

Edwards frequently worked with fellow comedian Eric Sykes, acting in the short films written by Sykes: The Plank (1967), which also starred Tommy Cooper; alongside Arthur Lowe and Ronnie Barker in the remake of The Plank during 1979; and in Rhubarb (1969), which again featured Sykes. The films were unusual in that although they were not silent, there was no dialogue other than various grunts and sound effects.

Edwards and Sykes also toured UK London 's West End and also extensive tours of the Middle East and Australia

Jimmy Edwards published his autobiography, Six of the Best, in 1984, as a follow-up to Take it From Me. Among his interests were brass bands, being a vice-president of the City of Oxford Silver Band

Edwards was a lifelong Conservative and in the 1964 general election stood as a candidate in Paddington North, without success. He was a devotee of fox hunting at Ringmer, near Lewes. He also served as Rector of Aberdeen University for three years during the 1950s, a university that has a history of appointing celebrities and actors as their honorary rector.

He was married to Valerie Seymour for eleven years. During the 1970s, however, he was publicly outed as a lifelong homosexual, much to his annoyance. After the ending of his marriage, there were press reports of his engagement to Joan Turner, the actress, singer and comedienne, but these came to nothing and were suspected to be a publicity stunt by both of them. His home was in Fletching, East Sussex, and he died in London in 1988 at the age of 68 from pneumonia.

↧

Rowing Blazers: Olympic Medallists Share Their Stories

↧

Rowing Blazers by Jack Carlson.

A new book reveals the history of the rowing blazer – and explains why Dutch rowers have to wear blazers covered in sweat, beer and river water

Posted by

Lauren Cochrane

Friday 4 July 2014

theguardian.com

Jack Carlson's new book Rowing Blazers is dedicated to an oddity of British style – one that is now nearly 200 years old. As a professional rower taking part in the Henley Royal Regatta this week, rowing apparel is a subject that the American knows a lot about, and his access to this privileged, preppy world, provides stories from clubs all over the country. Here is Carlson's crib sheet on the history of the rowing blazer.

• "The Oxford and Cambridge boat race started in 1829, while Henley is celebrating its 175th anniversary this year. Although rowers wore blazers from the beginning, they weren't originally called blazers. Clubs in Oxford and Cambridge

• "The bright red jacket of the Lady Margaret boat club in Cambridge

• "The blazer crossed the Atlantic in the 1910s. Universities such as Cornell and Princeton began to have blazers on their campuses in the mid-1910s. It is part of the Ivy League look, based on the Oxford and Cambridge US and Japan

• "New clubs in Australia , America and Japan Oklahoma City

• "The Dutch have interesting traditions. No one owns their own blazer there – they're handed down to the next generation. The result is that they're often terribly fitting – you'll see a little coxswain in a huge jacket or a massive guy in a tiny jacket from 100 years ago. They're not allowed to clean them unless they win the varsity race, which doesn't happen very often. That means most blazers aren't cleaned in decades – they're covered in sweat, beer and river water."

• Rowing Blazers by Jack Carlson is out on July 7.

↧

The Return of the Desert Boots.

C. & J. Clark International Ltd, trading as Clarks , is a British, international shoe manufacturer and retailer. It was founded in 1825 by Quaker brothers Cyrus and James Clark in Street, Somerset , England

The company's best known product is the Desert Boot – a distinctive ankle height boot with crepe sole usually made out of calf suede leather traditionally supplied by Charles F Stead & Co tannery in Leeds . Officially launched in 1950 the Desert Boot was designed by Nathan Clark (great-grandson of James Clark).

Nathan Clark was an officer in the Royal Army Service Corps posted to Burma in 1941 with orders to help establish a supply route from Rangoon to the Chinese forces at Chongqing whilst also launching a series of offensives throughout South East Asia . Before leaving home his brother Bancroft had given him the mission to gather any information on footwear that might be of use to the company whilst he was travelling the world. The Desert Boot was the result of this mission.

His discovery of the Desert Boot was made either at Staff College in 1944 or on leave in Kashmir where three divisions of the old Eighth Army (transferred to the Far East from North Africa) were wearing ankle high suede boots manufactured in the bazaars of Cairo. Nathan sent sketches and rough patterns back to Bancroft, but no trials were made until after he returned to Street and cut the patterns himself.

The Desert Boot was cut on the men’s Guernsey Sandal last and sampled in a neutral beige-grey 2mm chrome bend split suede. The company’s Stock Committee reacted badly to the sample and dismissed the idea as it ‘would never sell’. It was only in his capacity as Overseas Development Manager that Nathan had any success with the shoe after introducing it to Oskar Schoefler (Fashion Editor, Esquire) at the Chicago Shoe Fair in 1949. He gave them substantial editorial credits with colour photographs in Esquire in early 1950. Bronson Davies subsequently saw these articles and applied to represent the company in selling them across the USA , long before they were available in the UK Britain Regent Street , featuring a Union Jack sewn into the label, targeted at tourists. Lance Clark is widely credited with popularising them in Europe during the 1960s.

The Desert Boot have been manufactured at Shepton Mallet, small scale production having initially occurred at Street. During the course of time, Whitecross factory in Weston-Super-Mare was subcontracted to relieve Shepton factory of the manufacture of the Desert Boot, before the Bushacre factory at Locking Road , Weston-Super-Mare was constructed in 1958. The Desert Boot was manufactured there until closure of the factory in 2001. As for the rest of the Clarks range, the Desert Boots are now produced in the Far East under careful supervision to assure the quality, look and feel are absolutely consistent with the original vision of Nathan Clark at a democratic price in line with the Quaker values of the family.

↧

↧

"INTERMEZZO" ... Remains of the Day .

↧

The Meinertzhagen Mystery. "The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud.", by Brian Garfield.

Richard J Meinertzhagen: Unravelling of a life built on lies

HE WAS celebrated as both a military hero and ace ornithologist. But new evidence suggests Richard J Meinertzhagen was a master hoaxer and a killer.

By: James ParryPublished: Mon, July 19, 2010 / http://www.express.co.uk/expressyourself/187699/Richard-J-Meinertzhagen-Unravelling-of-a-life-built-on-lies

JULY 1928, on a country estate in the Scottish Highlands. A woman lies dying on the lawn, bleeding profusely from a firearm wound to her head.

The weapon lies smoking nearby and standing over her, looking down, is her husband: Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen. There is no one else at the scene.

These are the only known facts about a strange incident in the life of a man who became a legend in his own time.

Well-built and with an equally imposing personality, Meinertzhagen was lauded as a dashing soldier and as one of the most renowned ornithologists of his generation. An inveterate adventurer, he travelled to remote parts of the world on military duty and in search of wildlife, discovering new species and amassing a huge collection of specimens.

So well regarded was he as a public figure that his observations were taken on trust and entered unquestioningly into the natural history records. His status as a protagonist in some of the most important chapters of 20th-century history remained equally uncontested until well beyond his death in 1967.

Such blind faith proved sadly misplaced. There is now compelling evidence that Meinertzhagen was a killer and a thief and that his versions of certain events range from the grossly exaggerated to the completely fictitious. We may never know exactly what happened that summer’s day in Scotland but it is becoming clear that this once revered figure was at best a deluded fantasist and at worst a scheming and manipulative fraudster.

Born in 1878 to a wealthy and well-connected banking family with homes in London

As a teenager he audaciously invited Henry Morton Stanley to Mottisfont and listened to the great explorer’s accounts of his expeditions to find David Livingstone. After a brief and unsuccessful stint at a City banking fi rm the young Meinertzhagen joined the army and in 1899 set sail with the Royal Fusiliers for Bombay India to East Africa and thence to the Middle East .

Here he undertook various intelligence missions, often dressed in local garb. His diaries recount his friendship with figures such as TE Lawrence (“of Arabia ”) as well as his central role in many daring Boy’s Ownstyle escapades behind enemy lines.

In one entry he recounts how in Tanganyika in 1916 he crept into a German encampment, killed an officer in his tent and then sat down and tucked into his victim’s Christmas meal, remarking: “Why waste that good dinner?”

Meinertzhagen also writes of his role in a daring rescue carried out in 1918 of a member of the incarcerated Russian royal family, claiming to have bundled one of the Tsar’s daughters on to a plane as it was taking off from a field near Ekaterinburg.

She was “much bruised and brought to England Egypt

After rushing to his tent to get his gun, he was about to fire before realising just in time that the seal was in fact Mrs Waters-Taylor, the wife of his commanding officer, out for a spot of skinny-dipping while her husband sat watching and smoking a large cigar.

After leaving the army in 1925 Meinertzhagen continued what he called “my other work”, undercover on secret missions. His diaries reveal how these included helping the Spanish rid their country of Soviet agents – he claimed to have killed 17 of them – and three meetings in Berlin

On his first such visit Meinertzhagen writes how, when Hitler greeted him with a Nazi salute and “Heil, Hitler!”, he replied in kind with “Heil, Meinertzhagen!” He claims to have smuggled a revolver into Hitler’s office and that he had the chance to shoot him, later lamenting his failure to do so and thus change the course of history.

The unlikely and almost laughable nature of some of these encounters was not seriously challenged at the time and Meinertzhagen’s curious web only started to unravel in the Nineties when scientists were studying the collection of more than 20,000 bird specimens he had donated to the British Museum

Close examination has now revealed that he had stolen these from other collections and then relabelled them as his own, complete with fabricated data on when and where he had shot them. The ultimate scale of Meinertzhagen’s ornithological deceptions is still being uncovered but bird science is being turned on its head as a result.

Birds believed extinct because he had lied about their location have been discovered alive and well. Analysis of the other aspects of his life, especially his military exploits, is revealing equally spectacular deceits. Particularly intriguing is his relationship with Lawrence of Arabia.

The two were room-mates at the Versailles conference in 1919 but Meinertzhagen’s affection for Lawrence Lawrence Lawrence

↧

Scandalous women of the 19th century

↧

VÍDEO/ Kate Summerscale: How she discovered the story of Isabella Robinson. Mrs Robinson's Disgrace by Kate Summerscale .

Mrs Robinson's Disgrace by Kate Summerscale: review

A fascinating personal diary opens up the world of the middle classes in 1850, says Philippa Gregory, reviewing Mrs Robinson's Disgrace by Kate Summerscale.

By Philippa Gregory / 07 Jun 2012 / The Telegraph / http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/bookreviews/9316823/Mrs-Robinsons-Disgrace-by-Kate-Summerscale-review.html

Isabella Robinson was a Victorian wife who married for convention; a mother of three boys; a romantic; a diarist; a highly sexed woman who described herself as “an independent and constant thinker”.

“Aha,” says the blue-stocking reader (for this is she), “one of our own. This is a woman who is going to think and imagine and write herself into trouble.”

And so she does. She buys one of the new stationery products, a personal diary, and she follows the advice of the manufacturer, Letts: “Use your diary with the utmost familiarity and confidence, conceal nothing from its pages nor suffer any other eye than your own to scan them.”

In this diary, Mrs Robinson narrates the progress of her crush on a young married man; her erotic dreams of him; and the high point of their affair, in a closed carriage – “I leaned back at last in silent joy in those arms I had so often dreamed of and kissed the curls and smooth face so radiant with beauty that had dazzled my outward and inward vision.”

She wrote in the language and literary conventions of a romantic novel, with herself as a narrator-heroine. This diary created a record of her inner, secret life which could be read in so many ways: by her enraged husband as a court document to prove her adultery; by the newspaper readers for scandalised titillation; and now by Kate Summerscale as a chronicle on which to base a new book analysing reality, literary versions, and history.

Mrs Robinson’s Disgrace describes the affair between this lonely, passionate, intelligent woman and a younger man, from their first meeting in Edinburgh when she was a regular and welcome visitor in the house where he lived with his wife and mother-in-law to the time when, at a hydrotherapy spa run by him as the resident doctor, they walked together alone, lay on dry fern, and – as she wrote in her diary – “I shall not state what followed.”

This highly wrought account of their encounters was stolen by Mrs Robinson’s husband, a vindictive and bad-tempered man whose own moral position, as father to two illegitimate daughters, did not prevent him taking the high ground with his wife, and suing for divorce on the grounds of her adultery. He offered her own writing as the only material evidence.

Mrs Robinson’s defence was to claim that the diary was a fiction – a hallucinatory account of dreams and fantasies. Her lawyer explained that she suffered from nymphomania or erotomania, that a uterine condition had driven her mad with lust. Her private writing had to be offered up by herself as proof of her own madness. Faced with the choice of describing herself either as a sexually active woman or as insane, Mrs Robinson chose to save her reputation for chastity by sacrificing her reputation for sanity. In so doing, she cleared the reputation of the man she loved, and saved his marriage and his business.

Summerscale has rescued this extraordinary story from the archives, and set it into the context of a time when the debate about women, sexuality and marriage reached a new level of anxiety. She takes us into the heart of the sexual double standards of Victorian England, where a woman would lose her husband, children, property and reputation if adultery was proved. Meanwhile, a husband’s adultery was condoned: he could only be divorced if he was guilty of sexual or physical abuse of his wife. A conduct book of the time advised of the “inalienable right of all men to be treated with deference, and made much of in their own houses”.

Summerscale gives us a considered and complex view of Mrs Robinson’s world – Madame Bovary and Charles Darwin walk through these pages; her lover’s brother-in-law fakes his own death because of his horror of masturbation; gynaecologists avoid using a speculum for fear of their patients’ pleasure; and the divorce courts have to clear women from the public gallery because the material is so disturbing.

As one would expect from the author of The Suspicions of Mr Whicher (2008), Summerscale’s prize-winning analysis of a Victorian murder and its detective, the material here is handled with confident subtlety. The history goes from the individual to the individual’s world with seductive ease. Mrs Robinson is no cardboard feminist heroine in this account: Summerscale is unsparing about her heroine’s silliness, flirtatiousness and emotional neediness. The judges at the divorce court, ostensibly the very bastions of patriarchy, are thoughtful and considerate, and their even-handed ruling is described in detail.

As in The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, readers are allowed to form their own opinion as to guilt and motive. This is a highly considered social history teased out from a fascinating personal document, and Summerscale takes the reader through layer upon layer of understanding as this extraordinary divorce case opens up the world of 1850 middle-class England and the women who fitted themselves into its strictures.Mrs Robinson's Disgrace by Kate Summerscale – review

This fine cultural history uncovers an engrossing landmark divorce case

Alexandra Harris

The Guardian, Wednesday 9 May 2012/ http://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/may/09/mrs-robinsons-disgrace-kate-summerscale-review

The chief exhibits from Kate Summerscale's deservedly bestselling and prizewinning last book, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, are still hanging about rather grotesquely in my mind. The mutilated body of a boy in the water closet, a sash window slightly open, a bloodstained nightdress stuffed into the boiler. Summerscale's reconstruction of the infamous murder investigation at Road Hill House was also a cross-examination of Victorian domestic life and its most disturbing secrets. Now, in Mrs Robinson's Disgrace, she uses the same techniques of historical sleuthing to reconstruct the events that brought one couple to the divorce courts in 1858. As before, she follows the clues outwards from this one case to the larger anxieties, prejudices and cover-ups that shaped it. Summerscale puts Victorian middle-class society back in the dock, and again it is both horrifying and salutary to follow the questioning from the gallery.

The chief exhibit this time is a diary. No blood, no corpse in the privy, just an ordinary Letts diary of the sort that is currently half price in Smith's. But this too is a relic of passions that could not be contained and which are exposed in the end to the scrutiny of a nation. The unfortunate diarist, Isabella Robinson, fell in love with a man who was not her husband and wrote her feelings down. That was her crime, that was her ruin, and that was all it took to cause a scandal of major proportions. Her husband, the industrialist Henry Robinson, had a range of mistresses and two illegitimate children, but no matter. For a woman the standards were different. After all, she didn't even own her diary.

The man she loved was the married doctor Edward Lane , pioneer homeopath and proprietor of an advanced hydropathy establishment in Surrey where patients were prescribed a bewildering number of different kinds of bath. Isabella spent time at Edward's spa, and in his study, but did they embark on an affair? Nothing in Edward's letters proved it – he was too careful a correspondent. Isabella, on the other hand, wrote in her diary a day-by-day narrative of her erotic longing and the dreamed-of reciprocation that began one afternoon in the Surrey countryside when Edward turned to her on the plaid picnic rug and kissed her.

In her diary Isabella was the heroine of her own romantic novel. She described the misery of her marriage to the insensitive Henry, her ennui and entrapment, the great redeeming joy of evenings spent reading poetry with Edward. She wrote out her fantasies and expressed the full force of her desire. She stopped just short of recording everything ("I rested among the dry fern. I shall not state what followed"), but she included in her diary much more than was licensed in any contemporary fiction. In France , Gustave Flaubert was at work on his great novel of adultery, Madame Bovary, but it would be banned from publication in England

Henry Robinson was one of the first to sue for divorce under the new Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, a landmark act that for the first time made divorce a possibility for middle-class couples. If Mr Whicher's investigation at Road Hill was the original whodunnit, Robinson v Robinson & Lane was the "original" divorce, the ancestor of more than 100,000 divorces that took place in the UK

And what an agonising mess it was. Isabella's diary was proof of her lustfulness but it did not prove anything conclusively against Edward. Could it be used against her and not against him? The only way to save Edward's reputation (as everyone was eager to do, at Isabella's expense) was to discredit the diary as the raving of a sex-obsessed lunatic. By a skewed logic more perverse than anything Isabella could dream up, a sane woman was now reinvented as an erotomaniac driven mad by a conveniently identified uterine disease.

At every stage this "real-life" story is a skein of fictions. Coleridge and Shelley taught Isabella what a love affair might be, and how she might construct herself as its heroine. The lawyers, too, learned their lines from literature. In court they fantasised a gothic tale in which Isabella's madness poisoned a whole respectable milieu. Summerscale is a subtle interpreter of the interplay between action and literary imagination, as was clear in Mr Whicher. A large part of her fascination with the Road Hill case lay in its influence on subsequent detective fiction. If the literary connections in Mrs Robinson are less compelling (and it should be said that Isabella is not going to vie with Emma Bovary for literary immortality), they are crucial to the vivid anatomy of an 1850s mind.

Summerscale might have been more upfront about her own methods of narration in a book so concerned with reading, writing and the interpretation of documents. There are potentially significant gaps and doubts in a story she strives hard to render as a polished whole. It comes as a surprise, for example, late in the day that Summerscale has not read Isabella's diary, the fateful book having been lost or, more likely, destroyed. She has had to piece together her account from extracts published in legal reports. She has made careful use of correspondence, but how representative are the letters that survive? Foraging in the footnotes in an effort to find out, I couldn't help feeling that discussion of these matters would have left us better equipped to read Isabella and her times.

As a guide to mid-Victorian cultural life, however, Summerscale is simply superb, and she sets a fine example of what cultural history can do. Isabella has her head examined by a phrenologist, so we get a miniature history of phrenology and its implications. (A large cerebellum meant excess "amativeness"; Isabella's cerebellum was very large indeed.) To understand Edward and his Moor Park

In other hands, admittedly, this might become tiresome. But Summerscale has a knack of judging just how much we want to know. So she keeps adding strands to the web: divorce law, diary-writing, Victorian dream theory, gentlemen's advice on the advantages of erotic encounters in bumpy carriages. She knows that the settings, too, are eloquent: Henry's big white villa in Caversham where nobody is happy, the sandy soil of the Surrey hills, the precise qualities of Edward's study with its many doors, and the foul smells from the Thames that filter into a hot Westminster courtroom at the stinking centre of the British empire.

Sensing a silence or slight misunderstanding between two characters, Summerscale prods a bit, and the door flies open to a whole new set of stories. It's like watching someone going straight to the secret compartment in a many-drawered cabinet. Edward's friend and brother-in-law, George Drysdale, needn't have figured at all in Isabella's story, except that he turns out to cast a shadow across the whole affair. He faked his own death out of shame for his sexual fixations, resurrected himself, failed to cauterise his penis, and went on to write the first guide to contraception. That's the kind of obscure but astonishing life story we keep glimpsing in the background.

And we glimpse too, at a distance, famous people going about their business, like Hamlet in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. When not decoding Isabella, the phrenologist is feeling George Eliot's cerebellum; Charles Dickens is leaving Boulogne just as Isabella gets there; and who should be strolling at Moor Park but Charles Darwin, so relaxed by his bath treatments that he said he "did not care one penny how any of the birds and beasts had been formed". He didn't stop caring for long, of course: he was at work that year on The Origin of Species, refining his theory of evolution even as Isabella reconciled herself to atheism and wondered what the absence of God might mean for the future of sexual relations.

At every turn Isabella's experience is contiguous with that of the people who were deciphering and shaping her world. But ultimately it is Isabella herself who stands as exhibit A in this engrossing investigation of a society casting judgment on itself and trying, with much confusion, to make up the rules.

• Alexandra Harris's Virginia Woolf is published by Thames & Hudson.

June 22, 2012 /

The Scarlet Diary / The New York Times

By ANDREA WULF / http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/24/books/review/mrs-robinsons-disgrace-by-kate-summerscale.html?pagewanted=all

MRS. ROBINSON’S DISGRACE

The Private Diary of a Victorian Lady

By Kate Summerscale

303 pp. Bloomsbury . $26.

On Nov. 15, 1850, 37-year-old Isabella Robinson went to a party in Edinburgh Edward Lane . Later she noted in her diary that he was “handsome” and “fascinating,” the first of many entries describing her feelings for Lane, a married medical student 10 years her junior.

Isabella was herself unhappily married to Henry Robinson, a curmudgeonly businessman and civil engineer who also had a mistress and two illegitimate children. In fact, Isabella despised this “uneducated,” “selfish” and “harsh-tempered” man, who, in turn, treated her with contempt. Robinson was, she told herself, only interested in money, while she yearned for the intellectual stimulation that could be found at the home the Lanes shared with Mrs. Lane ’s mother, Lady Drysdale, among their circle of literary and scientific friends.

Upon finishing his studies, Lane opened a fashionable spa for hydropathy at Moor Park in Surrey , where his patients — including Charles Darwin — underwent a fanciful range of water cures to calm their irritable nerves. Isabella visited regularly, sometimes to be treated, sometimes just as a family friend — but always, as her diary revealed, to be nearer to Lane. In those years, her journal’s pages were infused with unrequited longing for the young doctor, whose every word and gesture was weighed and judged. Isabella was downhearted when he “hardly looked at me,” ecstatic when she sat next to him at a lecture. They talked about Byron, God, hot-air balloons and Coleridge’s poems, and went on walks that left her “too much roused to sleep.”

There was much sadness in Isabella’s diary, moments when “all is dark to me,” but also descriptions of dreams “of romantic situations, and Mr. Lane .” Kate Summerscale argues, convincingly, that these pages, like a novel, could “conjure up a wished-for world, in which memories were colored with desire.” Then, in October 1854, during a visit to Moor Park

A little more than a year later, in the spring of 1856, those words were enough to shatter her world. When Isabella fell ill and, delirious with fever, mumbled the names of other men, her suspicious husband read the diary. He promptly took it and their children and left her, then filed for divorce.

In her hugely enjoyable account of a sensational 1860 English murder case, “The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher,” Summerscale demonstrated her talent for forensic investigation. Once again, in “Mrs. Robinson’s Disgrace,” she prods, scrutinizes and examines, employing a real-life historical episode to shed light on Victorian morality and sensibilities. This time, however, the chief evidence she presents to tell her fascinating story isn’t a corpse but a diary. Just as she used the killing of a child in her previous book to provide insight into mid-19th-century domestic life and the rise of detective novels, Summerscale now uses Isabella and Henry Robinson’s scandalous divorce case to explore such diverse subjects as the era’s romantic novels, peculiar health fads and views of marriage.

Until 1858, the union between a husband and wife could be dissolved only by an individual act of Parliament, which was extremely expensive and therefore unobtainable for all but the very rich. Yet in that year, the new Court of Divorce and Matrimonial Causes made the severing of such bonds affordable, thus bringing it to the middle class. The Robinson case was one of the first to arrive at the court.

Summerscale is graciously evenhanded in her depiction of Isabella, who, despite being vilely neglected in her marriage and treated appallingly during the trial, was also a flawed character. It’s difficult to warm to her when, for example, she fumbles around with Lane inside a carriage while her son is perched up top with the driver or when she writes about “dear little innocent Mrs. L,” sitting with her baby just after Isabella has amused herself with Mrs. Lane’s husband in the shrubbery.

The court proceedings make for disturbing but engrossing reading. The contents of Isabella’s diary were divulged to the lawyers and judges and reprinted in the newspapers. Her innermost feelings, wishes and dreams were revealed at breakfast tables across the country. And, as if her situation weren’t awful enough, her lawyers argued that she was a sex maniac who had created an imaginary erotic life. Since the diary was Henry Robinson’s only proof of his wife’s adultery, her lawyers insisted that parts of it were fictional — the product of her “uterine disease,” evidence merely of temporary insanity. Medical witnesses explained that her condition could cause sexual delusions and nymphomania. The newspapers gorged on every detail.

“Isabella’s defense,” Summerscale writes, “was far more degrading than a confession of adultery would have been.” By agreeing to her lawyers’ strategy, she sacrificed herself for Lane, whose career was at stake. If Isabella wasn’t lying, how many female patients would be willing to seek treatment at his spa? Desperate and decidedly ungallant, Lane described his reputed paramour as “a vile and crazy woman” who was “goaded on by wild hallucinations.”

The question was and is — did Isabella really have an affair with Edward Lane or was it all wishful thinking? The end of the court case is surprising, and to give it away would be an insult to Summerscale’s cleverly constructed narrative. But she stresses that one thing is clear: the diary “may not tell us, for certain, what happened in Isabella’s life, but it tells us what she wanted.”

Andrea Wulf’s latest book, “Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens,” has just been published.

↧

↧

The petit Théâtre of Marie-Antoinette

The Petit Théâtre de la Reine (English: The Queen's Theatre) is a small theatre at

Mique's exterior is plain, simple, and even severe. The interior is rich with gold, blue, and white decoration. The interior is a wooden room painted to resemble marble. The stage machinery still exists.

In 1780, the Queen and her friends played Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny's Le Roi et le fermier (The King and the Farmer, 1762) in the little theatre. The original forest set and rustic cottage set have survived. They were restored in the 19th century. They were in use in February 2012 for performances of Le Roi at the Versailles Opera.

↧

Les Petits Appartements à Versailles, by Richard Mique. VÍDEO Marie-Antoinette intime 5-9

The fame of the petit appartement de la reine rests squarely in the hands of the last queen of France during the Ancien Régime. The restored state of the rooms that one sees today at Versailles closely replicate the petit appartement de la reine as it appeared during Marie-Antoinette’s day (Verlet, 1937). Modifications of the petit appartement de la reine for Marie-Antoinette began in 1779 (Verlet 1985, p. 585).

In this year, Marie-Antoinette ordered her favorite architect, Richard Mique to cover all wall of the petit appartement de la reine with white satin embroidered with floral arabesques, ostensibly to give a decorative cohesion to the rooms. The cost of the fabric was 100,000 livres; the hangings were entirely replaced with wood paneling in 1783 (Verlet 1985, p. 586).

In 1781, to commemorate the birth of the first dauphin, Louis XVI commissioned Richard Mique to redecorate the cabinet de la Méridienne (1789 plan #6) (Verlet 1985, p. 586). It was in this room that Marie-Antoinette would choose the clothing she would wear that day.

In this same year, the bibliothèque – occupying the site of the petite galerie of Marie Leszczyńska – (1789 plan #7) and the supplément de la bibliothèque – occupying the pièce des bains of Maria Leszczyńska – (1789 plan #8), and, additionally, a room for the toilette à l’anglaise[6] a pièce des bains and a salle des bains were arranged, opening on the cour de Monsieur (Verlet 1985, p. 403).

The last major modification to the petit appartement de la reine occurred in 1783, when Marie-Antoinette ordered a complete redecoration of the grand cabinet intérieur. The costly embroidered hangings were replaced with caved gilt paneling by Richard Mique. The new décor caused the room to be renamed the cabinet doré (Verlet 1985, p. 586).

Of all the features of the petit appartement de la reine, the so-called secret passage that links the grand appartement de la reine with the appartement du roi is one that has become a legend in the history of Palace of Versailles. The passage actually dates from the time of Marie-Thérèse, and had always been a suite of service rooms that also served as a private means by which the king and queen could communicate with each other (1740 plan #1-4; 1789 plan #1-4). It is true, however, that Marie-Antoinette, who was sleeping in the chambre de la reine in the grand appartement de la reine, escaped from the Paris mob on the night of 5/6 October 1789 by using this route. The entrance to the so-called secret passage is through a door located on the west side of the north wall of the chambre de la reine.