Mark Birley

Proprietor of private members' clubs who established a luxury brand with Annabel's, Mark's and Harry's Bar

Sunday 18 September 2011

Marcus Lecky Oswald Hornby Birley, club proprietor and businessman: born 29 May 1930; married 1954 Lady Annabel Vane-Tempest-Stewart (one son, one daughter, and one son deceased; marriage dissolved 1975); died London 24 August 2007.

Mark Birley had an unerring eye for the rightness of things: the shape of a room, the height of a table, the springing of an arch, the fall of a curtain and proper presentation of food. From his lofty perch – he stood 6ft 5in in his immaculately-cobbled shoes – nothing, whether a permanent or passing feature, escaped his glance.

It was this perfectionist perspective that made the private members' clubs he founded in London – Annabel's, Mark's and Harry's Bar principal among them – the finest of their kind in the world. And which made them last as long as they have. The Birley clubs have been the most sought after – for their setting, service and clientele – since the first of them, Annabel's, was opened as a night club in 1963. Collectively, they represented a grande luxe brand as impeccable as long-established names such as Cartier, Bulgari and Louis Vuitton.

At first, Birley had had modest ambitions for his first venture. He had worked in advertising, art-directing the Horlicks account for J. Walter Thompson in the early Fifties, and later for the French luxury-goods maker Hermes, while he and his wife, Lady Annabel Vane-Tempest-Stewart, brought up their young family. In December 1961, he was offered the lease of the basement of 44 Berkeley Square, in Mayfair, by their friend John Aspinall. Upstairs at 44, Aspinall was restoring William Kent's exquisite Palladian interior with the collaboration of the architect Philip Jebb and the decorator John Fowler, making it the setting for the Clermont Club, gaming den for London's high rollers. It was a restoration project that set new standards for post-war London.

Accepting the lease of the basement, just two rooms deep, Birley thought of setting up a small piano bar. He took on Jebb as his architect, but did not invite the imperious Fowler on board, getting help with the decoration from the Peruvian artist Pedro Leito. Birley had all the talents to be his own decorator, or indeed his own architect, and when he invited collaboration it was with sympathetic partners. Jebb, like Birley still in his early thirties, had already done extensive interiors work in London, turning Belgravia houses into flats for Birley's friend Douglas Wilson. Jebb suggested to Birley that they should extend the basement as far back as 44 Hay's Mews by digging out the garden, involving the hand-barrowing of tons of London clay.

The nascent piano bar could thus become a full-blown night-club. It was named after Annabel Birley. The club has always been a striking spacial experience, at once intimate but theatrical. The visitor comes down the area steps, under a heavy blue and gold awning, and into a small lobby. From here a carefully modulated spinal corridor runs to the dance floor at the back, passing the Buddha room on the left side, the private dining room on the other, and the main bar and dining area.

Mark and Annabel Birley, one of the most glamorous married couples in London, attracted a raft of their upper-crust friends to be founding members. The club was an immediate success, and became a great meeting place for swinging London, but no one thought the place would stay open for more than a short period, still less for 44 years and counting. The Clermont and Annabel's made 44 Berkeley Square the grandest evening-out address in London. Sadly, Birley and Aspinall fell out in tumultuous fashion over Aspinall's wish to use part of the basement as a wine cellar for the Clermont. Aspinall recalled that the sole witness of their argument described Birley as red with anger and Aspinall white with rage. There remained a lasting chill between them, although the two men were, according to Aspinall, in friendly contact by letter in the years before Aspinall's death in 2000.

Birley's secret was day-to-day presence; being on hand to make decisions as Annabel's became established. As he told the writer Naim Attalah in 1989:

It's not so much perfectionism I'm after in the way I run Annabel's, as the way I think things ought to be. I just want to get everything right in the way I think to be best. Of course it is a matter of going on and for years and staying interested enough to try to improve things. I'm not good on committees. One of my failings is a lack of patience. I'm used to taking my own decisions... That rather autocratic way of running things has advantages and disadvantages but one of the main advantages is that makes for speed and makes your employees happier I think. They like somebody who can say yes or no.

At Annabel's, Birley never let things stand still. A private dining room was added, and a new bar. And all the time, under the watchful gaze of the superb maître d'hôtel Louis, staff remained discreet about the members' private liaisons. As the writer Candida Lycett Green recalled, everyone at the club was slightly in love with Birley

It's something about his elusiveness; the way he looks so inexorably sad; the way his suits are immaculately cut; the way his eye for a picture never falters and a certain wild bohemianism hovers in his closet.

That artist's eye, that sense of that lurking bohemianism, was Birley's heritage as the son of the portrait painter Sir Oswald Birley and his redoubtable wife Rhoda Pike. Sir Oswald was the favourite artist of the royal family, society figures, and of Winston Churchill, with whom he spent painting holidays. The Birleys were patrons of the Russian ballet. They had a Clough Williams-Ellis villa in St John's Wood, and Charleston Manor, a perfect small Georgian house near West Dean in Sussex.

Mark was educated at Eton, and spent one year at Oxford, where his future wife first encountered him, and was struck by his youthful air of languid self-possession. In London, they met again, and Annabel noticed Mark "swirling deb after deb" around the dance floor. They fell in love at Queen's ice-skating rink, were married in 1954, and their first son, Rupert, was born in 1955.

One of their first married homes was the exquisite Pelham Cottage, half of a hidden Georgian farmhouse close to South Kensington tube station. Mark took charge of the alterations to the house, one of his earliest collaborations with the architect Philip Jebb.

Birley and Jebb started work on a second club, Mark's, at 46 Charles Street, around the corner from Annabel's in 1969. Mark's is a hushed lunching and dining club, in a converted Edwardian townhouse. In 1975 Birley took a lease on a former wine merchant's shop at 26 South Audley Street, 200 yards northwest of Annabel's. Here, he and Jebb created Harry's Bar. The name came from the famous Cipriani hostelry in Venice. But, in Birley's view, his was a far more ambitious undertaking.

His Harry's Bar was to be a meeting place, a private restaurant for the special Birley clientele. The dining room there, he felt, was the most beautiful room he had created thus far. The special feature is its low seating, and the spacing of the tables, all to generate the feel of an alfresco meal. The opening of Harry's Bar was probably Birley's apotheosis, where he and his friends brought the Birley brand to its highest pitch. Afterwards Birley created George, another dining club, and the Bath & Racquets Club, a gentleman's gymnasium.

Birley was courted by many international associates who wanted him to take Annabel's international. There was a hotel project in Malta; approaches to create an Annabel's in Hong Kong, another in Mexico City; the Ritz in Paris asked him to set up an English bar. None of these projects came to fruition. And probably just as well, as Birley knew that the success of his brand depended on detailed personal supervision, something that would have suffered with any sort of international spread to his empire.

Birley widened his net from clubs to shops in London: an interiors emporium in Pimlico Road, in collaboration with the decorator Nina Campbell, in 1973, and Birley & Goodhuis, a cigar and wine shop, in the Fulham Road in 1978.

His son Robin added to the family brand when he opened his first Birley's sandwich bar in Shepherd Market, Mayfair. The business really took off when Robin launched branches in the City of London soon after, but from the first his menu of exotic, good ingredients, hand-assembled with edible bread, revolutionised lunchtime eating in London. It has been much imitated globally.

Mark Birley was a friend and patron of artists: his mother's contemporary Adrian Daintrey; the glass engraver Lawrence Whistler; and the portraitist John Ward. In 1983 Ward produced a triptych of the founding members of Annabel's to mark the club's 20th anniversary. Birley liked cars. When Annabel's held a members' raffle in the early days, the first prize was an Aston Martin DBS. In the 1970 World Cup rally, from London to Mexico, he co-piloted a Mercedes with the racing driver Innes Ireland. And they led during the early European stages, until their brake fluid boiled, the car became undriveable, and their race ended, Birley at the wheel, nosefirst against a roadside tree.

For all his old-Etonian bon ton corrrectness, Birley had something raffish, self-branding and up-to-date about him. His cars, all with an MBA number plate, could be seen parked outside his office or his house. His transatlantic social life meant he kept abreast of new trends in the Seventies and Eighties, sporting a Sony Walkman or working out with weights before either had become universal phenomena. Throughout these years, young men on the make in banking or property aped his manners in the hope of finding social prominence.

For the past four decades he lived at a series of houses in South Kensington: first Pelham Cottage; a house around the corner in Pelham Street after he and Annabel were separated (they divorced in 1975, when she married the business magnate Sir James Goldsmith); and Thurloe Lodge, opposite Brompton Oratory, his final home.

At Thurloe Lodge there was much work to be done. At first Birley perched in a small sitting room, and he and Jebb did up rooms in turn as money allowed. Jebb brought Birley back into contact with Tavener & Co, London's leading builders and joiners. The firm had done work for Sir Oswald and Lady Birley, and the brilliant Roger Tavener – part of the Beatles circle and brother and backer of the composer John – thus became the third generation of his family to work with the Birley clan.

In Birley's houses, as much as in his clubs, there were multiple reminders that he was the son of two artists. At Thurloe Lodge, in its well-set, square drawing room, he made a marvellous setpiece, where his hanging of Edwardian art was all of a kind. In its homogenous initial impact it was as arresting as any comparable drawing room in London: Sir Brinsley Ford's salon of Richard Wilson landscapes in Mayfair; Lady Diana Cooper's run of portraits of herself by Ricketts, Shannon and McEvoy in Warwick Avenue; or Linley Sambourne's room of his own drawings for Punch magazine, now preserved as museum in Stafford Terrace, Kensington.

Birley suffered a shattering blow in 1986 when his son Rupert disappeared while taking a morning swim while working in Lomé, west Africa. His body was never recovered. Birley organised an emotional funeral at St James's Piccadilly, where the singing of the Inspirational Choir made a heartbreaking occasion more moving still.

Towards the end of his life, Mark Birley was regularly in ill-health, and spent long periods in the Cromwell Hospital. He passed the running of Annabel's to his children Robin and India Jane, who did much to revive the membership of the venerable flagship. In June, the entire Birley fleet of clubs was sold for a reported £90m. The Birley brand had remained intact to the end.

Louis Jebb

Mark Birley's art treasures for auction

The contents of the Annabel's club owner Mark Birley's house are coming up for sale at Sotheby's, six years after his death

By Matthew Dennison8:00AM GMT 26 Jan 2013

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/9824189/Mark-Birleys-art-treasures-for-auction.html

Lucian Freud once admitted that he had considered Mark Birley – son of the society portraitist Oswald Birley, Old Etonian doyen of smart London nightclubs, brother of Maxime de la Falaise and, famously, cuckold of Jimmy Goldsmith – 'a very cold man' until he went to his house.

The house in question stands four square and early Victorian, of dun-coloured brick leavened with wisteria, opposite the Brompton Oratory, a stone's throw from the Victoria and Albert Museum and Harrods. It was Mark Birley's home for nearly 30 years, until his death in 2007. Externally unrevealing, architecturally decorous, discreetly, expensively elegant, Thurloe Lodge appears a reflection of Birley himself: understatedly urbane, debonair. Perhaps, even, at a push… cold. Internally, however, in Birley's day the house presented a different portrait of its owner from that offered to the passer-by, revealing in comfortable, suggestively opulent interiors that warmth which surprised Freud. Its plumply upholstered rooms, densely hung with pictures and crowded with objects, betrayed a sensuousness at odds with that aloofness bordering on curmudgeonliness detected by Birley's detractors: bronzes, china and masses of fresh flowers coalesced into a backdrop more sybaritic than spartan.

This spring, 50 years after the opening of Birley's first and best-known club, Annabel's, and a year on from the sale of Thurloe Lodge itself, the contents of the house will be offered for sale by Sotheby's. Lots include paintings by Augustus John and William Orpen, drawings by Rossetti and David Hockney, a Mac cartoon about Annabel's originally published in the Daily Mail, and a Cartier tie pin.

The decision to sell was taken by Birley's daughter, the artist India Jane, for practical reasons: there is simply too much stuff to be accommodated in India Jane's own London house and her house in the country. Although she has kept a number of pieces, including a self-portrait of her grandfather and several small bronzes by Bugatti, she approaches the sale with mixed emotions. It is no secret that, following an acrimonious family rift which saw India Jane's surviving elder brother, Robin, effectively disinherited, Birley senior's chief legatee is his only grandson, India Jane's seven-year-old son, Eben. In accordance with the terms of Mark Birley's will, proceeds of the sale will be placed in trust for Eben until he attains his majority.

It is ironic that the will, which lies at the centre of the present sale, should have supplied such wellsprings of material for gossip columnists on both sides of the Atlantic. Birley's success lay in his stylish yet unassertive reinvention of London's nightlife, beginning in the early 1960s. Annabel's Club came first, in 1963, in the basement of a William Kent house in Berkeley Square, occupying a relatively small space once given over to wine vaults. It was named after Birley's then wife, Lady Annabel Vane-Tempest-Stewart, whom he had married in 1954 (and who would later leave him for their mutual friend Jimmy Goldsmith).

From the beginning, the look was dubbed 'country house style': walls plentifully hung with pictures or panelled, with soft banquettes for seating. In fact it was anything but – too smart, comfortable and stylish for the average English country house in those first decades after the war. A school friend, Peter Blond, remembers that even at Eton, Birley was determined to open a nightclub. At the age of 33, married with three young children, he achieved his dream. For Blond, the success of Annabel's was certain, its sophisticated indulgence contrasting with 'the ghastliness of post-war London nightclubs, with awful seedy pink lampshades and no pictures. Such a shortage of elegance and style.'

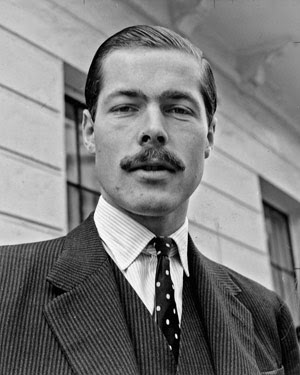

Assiduously Birley and his founder members gathered around them the great, the grand, the glamorous and the glittering, many of them relations or near relations of Birley and his wife. 'He knew he needed lots of glamorous people to make the clubs work,' India Jane says. He played host to guests who included the Queen, Lord Lucan, Aristotle Onassis, Frank Sinatra and President Nixon. In their wake followed flotillas of the socially aspirant. Prices were consistently vertiginously high – Birley once upbraided a couple from the North who protested at their lunch bill, pointing out that his Harry's Bar was no place to eat on an economy drive. In return, guests could expect the best of the best and the highest levels of service. It was, after all, only what Birley wanted and expected for himself.

He spent every night at Annabel's. Later he would divide his time among all five of his clubs (after Annabel's he opened Mark's Club, Harry's Bar, George and the Bath & Racquets Club), and no detail was too small for his forensic attention, from the way butter was curled to the choice of glass and, famously, the wrapping of lemon chunks in muslin to contain their pips. As Blond comments, 'He was very, very aware of how things should be done.'

On paper such an approach smacks of snobbery, an etiquette-book approach to life. In practice Birley's outlook was as much to do with ennui, snobbery the fallback position. 'Mark was easily bored,' one friend remembers. 'That impatience created the discipline that ran the clubs so well.' In 1963 Annabel's was remarkable among upper-class London nightspots in not requiring a dinner jacket; later Birley abolished the requirement for a jacket and tie, but afterwards gave in to popular pressure and reintroduced it.

India Jane describes her father as 'very modern'. His concern extended beyond the old apparatus of social hierarchies and, despite his huge professional acquaintanceship, he contrived not to appear overtly social. Save for a talent for drawing which expressed itself most often in sketches of women's legs complete with high-heeled shoes, he was an unlikely nightclub denizen. 'He wasn't the easiest of people and not the congenial club owner in any sense of the word,' Blond remembers. But the stock-in-trade of the Birley empire, like that of Birley's own life, was the pursuit of pleasure.

His small stable of nightclubs and eateries offered their well-heeled, well-connected, occasionally well-known clientele many blandishments, not least discretion. In the ladies' room at Annabel's, for example, the formidable Mabel, lured by Birley from Wilton's, was said to be able to distinguish between a wife and a mistress at a single glance and, if need be, to ensure that the two did not encounter one another. It was all part of the service and typical of that fastidious, indeed obsessive attention to detail that earned Birley a reputation for perfectionism, which he himself preferred to describe as 'just want[ing] to get things right in the way I think to be best'.

Sir Edwin Landseer, The Poor Dog (The Shepherd’s Grave), est £25,000-35,000; Charles Burton Barber (1854-1894), Good Friends, £80,000-120,000. Courtesy of Sotheby's

'For my father, perfectionism meant his perfect idea of beauty,' India Jane remembers, 'but it was a concept that embraced an edge of imperfection. He had an incredibly broad, grand approach and his was a painter's perfection: if the colour of a lampshade was wrong, he would change it like an artist changes the colour in a painting.' And so Birley's collection includes a handful of works of the highest quality – David Hockney's 1993 pencil portrait of a dachshund, Boodgie (£12,000-18,000), and Sir Edwin Landseer's The Poor Dog (£25,000-35,000), one of four Landseers included in the sale. Birley claimed that it was among Landseer's very best pictures, painted 'before Queen Victoria got hold of him'.

In another instance he followed happily in Queen Victoria's wake. Good Friends, of 1889 (£80,000-120,000), an image of a small girl and a large St Bernard dog, is a first-rate example of the work of Charles Burton Barber. A leading animal portraitist, Barber spent much of the last quarter of the 19th century employed by the Queen to record her vast kennel of many breeds. One club regular remembers the painting in Mark's Club. Birley frequently moved paintings and objects between his home and his clubs – a blurring of the distinction between work and play, art and life, stage and gallery.

Thurloe Lodge also offered Birley levels of comfort bordering on sumptuousness. The interior designer Nina Campbell, who redesigned Annabel's Club in her early 20s, went on to open a shop with Birley on Pimlico Road selling Fauchon sweets and luxury linen, and afterwards worked on other Birley venues, describes his 'wonderful ways of making things comfortable'. In the five years after his purchase of the house in 1980, he converted the four-bedroom family home into a space ideally suited to his own needs and those of the succession of dogs with whom, with greater effusiveness than he appeared to reserve for any person, he shared his life. Its large, square drawing-room opening on to a panelled dining-room, remembered by India Jane as 'so ravishingly beautiful', successfully combined a hedonist's instinct for personal comfort with an old-fashioned eschewal of ostentation: deep sofas surrounding a crackling log fire were serviced by a plethora of drinks tables and low-level lighting. In the background walls covered in a distinguished collection of mostly 19th-century, mostly canine paintings suggested the successful anglicisation of a decidedly Proustian mise-en-scène.

If the effect was rich, it was an old-money richness unconcerned with anything outside its own four walls. It was the same look Birley repeatedly brought to his clubs and key to the success of those ventures which, despite an element of hauteur, were at the centre of London social life throughout the Swinging Sixties. In the decoration of his home Birley was guided exclusively by personal preference. Ignoring changing fashions, he was happy to indulge magpie instincts which he orchestrated with flair and taste. 'My own passion for collecting is a sort of acquisitiveness, I suppose,' he once admitted. 'If I had time to go around all the salesrooms, there would be no end to the stuff I could get interested in.' As India Jane remembers, 'He did everything to suit himself precisely. Not for the clubs' members but always to please himself.' It made for a vision undiluted by compromise – and one that, from the outset, became instantly recognisable and instantly popular.

India Jane Birley is not selling the entire contents of Thurloe Lodge. A recent purchase has enabled her to keep a selection of pieces from her father's collection. For India Jane has bought Charleston Manor, the house in Sussex which formerly belonged to her grandparents, Oswald and Rhoda Birley. Eleventh-century in origin, remodelled in the 18th century, it has small rooms with long views. 'It was the house I went to now and again as a child and easily the most significant place I knew,' she recalls. It was also, she feels, the principal influence on her father growing up and the house to which his thoughts turned repeatedly at the end of his life.

Today the house is once again embellished with paintings by Oswald Birley, alongside an antique tapestry and a 17th-century refectory table latterly housed at Thurloe Lodge. It provides for India Jane a sense of coming home. But it is not only she who has returned. With her are her father's last, beloved dogs, Tara, an 18-year-old alsatian, and George, a 16-year-old labrador. Surely, too, something of her father has returned to the Sussex of his childhood along with his daughter and only grandson. 'Pup's ghost must be fluttering about…'

Mark Birley – The Private Collection is at Sotheby's on March 21 (020-7293 5000; sothebys.com)

|

A mock-up of the drawing room in Thurloe Lodge. Friends and relatives are devastated that India Jane has sold items that Mark Birley spent a lifetime collecting Photo: EDDIE MULHOLLAND |

Mark Birley: 'His things were thrown to the wolves’

India Jane Birley’s auction of her father’s belongings has outraged her brother Robin and deepened the family feud

By Sarah Rainey8:36PM GMT 22 Mar 2013

The original version of this article on 22 March said that Robin Birley had been the subject of allegations that he had stolen money from his family business. We accept that no money was stolen by Mr Birley and we apologise unreservedly to Mr Birley. The reference has been removed.

Tucked away in a discreet corner of South Kensington is Thurloe Lodge, the £17 million former home of Mark Birley, founder of the exclusive London nightclub Annabel’s. Creeping wisteria clings to its fawn-coloured bricks, its neat front garden edged with trimmed hedgerows and spring flowers. Large vaulted windows, their frames painted pristine white, are draped with heavy curtains, as if concealing treasures within.

For nearly 30 years, Thurloe Lodge was a shrine to Birley’s life. An arbiter of taste and avid collector of art and antiques, the house was a catalogue of his finest acquisitions. Inside, an elegant drawing room opened on to a panelled dining hall, where deep sofas faced a marble mantelpiece. The table was impeccably set with silver cutlery, even when Birley dined alone, and a Hermès backgammon board, personalised with a tapestry surface so the dice wouldn’t rattle, sat open by the window, ready to play should friends call round.

Fires always crackled in the grates. The lighting was soft, echoing the dimly lit interiors of Annabel’s, and the air teemed with cigar smoke. The walls were a jigsaw of paintings – a Hockney, a Rossetti, several Munnings – and hand-picked artefacts from around the world were propped up on low tables: china figurines; cocktail shakers; monogrammed cigar boxes.

In 2011, four years after his death, India Jane, Birley’s only daughter, sold Thurloe Lodge. Then, on Thursday, she put the contents of the house up for auction at Sotheby’s in London. More than 500 objects went under the hammer, among them Birley’s most personal belongings: hairbrushes, tie pins, signed paintings of his dogs by the artist Neil Forster.

Now, friends and relatives – including her brother Robin, from whom India Jane is said to be estranged – are devastated she has got rid of items that Birley spent a lifetime collecting. “It was,” one admits, “like [his possessions] were thrown to the wolves.”

In the auction room, a wooden statue of Birley’s beloved dog Blitz (Lot 171, sold for £26,000), was placed at the front, as if standing guard over his master’s property. Lot 460, a collection of gentleman’s dressing accessories, including three ivory hairbrushes engraved with an “M”, sold for £3,800. His four-seated red sofa; a hat stand; silverware; the contents of his wine cellar; even his bath fittings (Lot 485, green and silver Art Deco taps) – all went to new homes. There was a heated bidding exchange for Lot 232, the prized backgammon board, which eventually went to a telephone bidder for £16,000, 10 times its estimate.

Some of Birley’s friends were present, hoping to stop his possessions falling into the hands of strangers. But his son Robin, 55, refused to attend, branding the auction a “tragedy”.

“I want nothing to do with it, and no one in my family will have anything to do with it,” he sighs. “Everyone is appalled. I could understand if my sister was desperately in need, but the opposite is the case. Why not treasure his things? Why not give things away to staff who worked for my father for 30 years? Why not give things away to his friends? All these things financially mean little to her and a tremendous amount to them. I think it’s pitiful.”

In 2006, Robin was unceremoniously cut out of his father’s will. Birley, who died aged 77, left the bulk of his £120 million fortune to India Jane, in trust for Eben, her son, with Robin getting a token £1 million – a share that later rose to £35 million after an out-of-court settlement.

India Jane, 52, says she sold her father’s belongings because there were simply too many to fit into her London home and her new country estate, Charleston Manor in East Sussex. Friends suggest her father’s possessions were also “too grand” for her tastes. Explaining her motivations for the auction in the Sotheby’s brochure, India Jane admits it was a “difficult decision”. “I like to think [my father] approves of the sale, for being an artist he understands my need to carve out my own space,” she adds.

But David Wynne-Morgan, a PR guru and one of Mark Birley’s oldest friends, disagrees. “She is completely wrong,” he insists. “I mean, he told me. I lived in his cottage, I was on his board for 40 years. I was very close to him. He was ill at the end, his mind was not good and his short-term memory had gone. But I did say to him, 'Why did you change your will and leave the house and everything to India Jane?’ And he said, 'Well, I think she will treasure the house and its contents.’”

The Birley family’s history is marred by tragedy, rifts and betrayals. Mark’s eldest son, Rupert, disappeared aged 30 while swimming off the coast of West Africa in 1986. At the age of 12, Robin was mauled by a tiger at a private zoo in Kent, leaving him facially scarred. It is rumoured that he and his father never resolved their disagreement over the rewriting of his will; Mark famously kept a scathing letter from Robin in his jacket pocket, in which his son disowned him as a father. Robin, having made his money from a lucrative chain of sandwich shops, is now a nightclub owner himself, having opened 5 Hertford Street in Mayfair last June.

And there is another side to the extended family. Mark’s wife, Lady Annabel, had two children with his friend Sir James Goldsmith (writer Jemima Khan, and Conservative MP Zac) during their marriage. She divorced him in 1975 and married Goldsmith (with whom she had a third child, Ben) in 1978. When approached by The Daily Telegraph this week, neither Lady Annabel nor any of the three Goldsmith children wanted to comment on the auction.

Willie Landels, the founder of Harpers & Queen magazine and a long-term friend of Mark’s, says he understands why family members would rather distance themselves from the sale. “It is not for us to talk about; it is not our place,” he says. “Obviously when there’s so much stuff it has to be sold, but there were some things that were very personal to Mark, like his brushes. I find the whole thing rather sad… It was like they were thrown to the wolves.”

Landels was not at the auction on Thursday, but Wynne-Morgan was, along with Nina Campbell, the interior designer who worked with Birley on the décor of Annabel’s. “When you’ve known somebody incredibly well and known the house well, there is a sort of sadness when you see these things that you’ve known or you’ve sat on or you’ve looked at or you’ve drunk out of or you’ve eaten off, suddenly stripped down,” says Campbell.

She is careful not to criticise India Jane, adding: “Mark was an inveterate shopper, so there’s tons of stuff. She’s kept the things that mean something to her and hopefully the other things will have gone to a good home to be used by people who love them.” Sir Evelyn de Rothschild, another close friend of Birley’s, agrees that there was “an awful lot in his home”. He adds: “The auction was an example of what [Mark] collected and his joy of dogs.”

Wynne-Morgan, however, found a preview of the auction, attended by a number of Birley’s friends, “rather uncomfortable”. “India Jane is perfectly entitled to do what she likes,” he concedes. “But it was a very strange thing, seeing all these things set out. I find it a great pity. I mean that house; he created it. The man’s taste was quite amazing. He did it superbly well. I think it would have been nice for it to have been handed down to future generations and for it to be seen as a symbol of what he’d done.”

Birley had many loyal staff at Thurloe Lodge, including housekeeper Elvira Maria and his butler, Mohamed Ghannam. Wynne-Morgan is disappointed that India Jane didn’t give more of her father’s personal belongings to them. “He loved getting Christmas presents from the staff. We used to give him things, usually in silver, often with all our signatures engraved on them. An awful lot of those have been sold. The employees I talked to were horrified.”

Such sadness pervaded the Birley sale. Remnants of the old Annabel’s (now owned by restaurateur Richard Caring) – pastel drawings, posters commissioned for the cloakrooms – were sold to anonymous bidders. Several of Birley’s friends walked out when they failed to win lots – in Wynne-Morgan’s case, his backgammon board. “I reckon I lost about £30,000 to him over the years, because he was a much better player than me,” he recalls. “He used to say, 'David, you were terribly unlucky tonight.’”

Luck didn’t come into it: the auction was an unprecedented success, raising £3.85 million – money that will be put into trust for Eben until he turns 18. A fitting tribute, some might say, to the man who for 40 years put on London’s finest parties: even in death, Birley can throw the best auction in town.