In July 1889, the Metropolitan Police uncovered a male brothel operated by Charles Hammond in London Cleveland Street

The resultant Cleveland Street London

The Prince of Wales intervened in the investigation; no clients were ever prosecuted and nothing against Albert Victor was proven. Although there is no conclusive evidence for or against his involvement, or that he ever visited a homosexual club or brothel,[38] the rumours and cover-up have led some biographers to speculate that he did visit Cleveland Street,[39] and that he was "possibly bisexual, probably homosexual".[40] This is contested by other commentators, one of whom refers to him as "ardently heterosexual" and his involvement in the rumours as "somewhat unfair". The historian H. Montgomery Hyde wrote, "There is no evidence that he was homosexual, or even bisexual."

The rumours persisted; sixty years later the official biographer of King George V, Harold Nicolson, was told by Lord Goddard, who was a twelve-year old schoolboy at the time of the scandal, that Albert Victor "had been involved in a male brothel scene, and that a solicitor had to commit perjury to clear him. The solicitor was struck off the rolls for his offence, but was thereafter reinstated." In fact, none of the lawyers in the case was convicted of perjury or struck off during the scandal, but Somerset's solicitor, Arthur Newton, was convicted of obstruction of justice for helping his clients escape abroad, and was sentenced to six weeks in prison. Over twenty years later in 1910, Newton Newton

During his life, the bulk of the British press treated Albert Victor with nothing but respect and the eulogies that immediately followed his death were full of praise. The radical politician, Henry Broadhurst, who had met both Albert Victor and his brother George, noted that they had "a total absence of affectation or haughtiness". On the day of Albert Victor's death, the leading Liberal politician, William Ewart Gladstone, wrote in his personal private diary "a great loss to our party". However, Queen Victoria referred to Albert Victor's "dissipated life" in private letters to her eldest daughter, which were later published and, in the mid-20th century, the official biographers of Queen Mary and King George V, James Pope-Hennessy and Harold Nicolson respectively, promoted hostile assessments of Albert Victor's life, portraying him as lazy, ill-educated and physically feeble. The exact nature of his "dissipations" is not clear, but in 1994 Theo Aronson favoured the theory on "admittedly circumstantial" evidence that the "unspecified 'dissipations' were predominantly homosexual".Aronson's judgement was based on Albert Victor's "adoration of his elegant and possessive mother; his 'want of manliness'; his 'shrinking from horseplay'; and his 'sweet, gentle, quiet and charming' nature", as well as the Cleveland Street rumours and his opinion that there is "a certain amount of homosexuality in all men". He admitted, however, that "the allegations of Prince Eddy's homosexuality must be treated cautiously."

Rumours that Prince Albert Victor may have committed, or been responsible for, the Jack the Ripper murders were first mentioned in print in 1962. It was later alleged, amongst others by Stephen Knight in Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, that Albert Victor fathered a child with a woman in the Whitechapel district of London, and either he or several high-ranking men committed the murders in an effort to cover up his indiscretion. Though such claims have been repeated frequently, scholars have dismissed them as fantasies, and refer to indisputable proof of the Prince's innocence. For example, on 30 September 1888, when Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes were murdered in London, Albert Victor was over 500 miles (over 800 km ) away at Balmoral, the royal retreat in Scotland, in the presence of Queen Victoria, other family members, visiting German royalty and a large number of staff. According to the official Court Circular, family journals and letters, newspaper reports and other sources, he could not have been near any of the murders. Other fanciful conspiracy theories are that he died of syphilis or poison, that he was pushed off a cliff on the instructions of Lord Randolph Churchill or that his death was faked to remove him from the line of succession.

Albert Victor's posthumous reputation became so bad that in 1964 Philip Magnus called his death a "merciful act of providence", supporting the theory that his death removed an unsuitable heir to the throne and replaced him with the reliable and sober George V. In 1972, Michael Harrison was the first modern author to re-assess Albert Victor and portray him in a more sympathetic light. In recent years, Andrew Cook has continued attempts to rehabilitate Albert Victor's reputation, arguing that his lack of academic progress was partly due to the incompetence of his tutor, Dalton; that he was a warm and charming man; that there is no tangible evidence that he was homosexual or bisexual; that he held liberal views, particularly on Irish Home Rule; and that his reputation was diminished by biographers eager to improve the image of his brother, George.

The conspiracy theories surrounding Albert Victor have led to his portrayal in film as somehow responsible for or involved in the Jack the Ripper murders. Bob Clark's Sherlock Holmes mystery Murder by Decree was released in 1979 with "Duke of Clarence (Eddy)" played by Robin Marshall. Jack the Ripper was released in 1988 with Marc Culwick as Prince Albert Victor. Samuel West played "Prince Eddy" in The Ripper (1997) and Albert Victor as a child (with Jerome Watts and Charles Dance playing the character at older ages) in the TV miniseries Edward the Seventh, which starred West's father Timothy West as the title character. The Hughes brothers' From Hell was based on the graphic novel of the same name by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell, and was released in 2001. Mark Dexter portrayed both "Prince Edward" and "Albert Sickert". The story is also the basis for the play Force and Hypocrisy by Doug Lucie.

A pair of alternative history novels, written by Peter Dickinson, imagine a world where Albert Victor survives and reigns as Victor I. In Gary Lovisi's parallel universe Sherlock Holmes short story, "The Adventure of the Missing Detective", Albert Victor is portrayed as a tyrannical king, who rules after the deaths (in suspicious circumstances) of both his grandmother and father. The Prince also appears as the murder victim in the first of the Lord Francis Powerscourt crime novels Goodnight Sweet Prince,[108] and as a murder suspect in the novel Death at Glamis Castle by Robin Paige. In both The Bloody Red Baron by Kim Newman and the novel I, Vampire by Michael Romkey, he is a vampire. In the former, he is the British monarch during World War I.

"Set against the vivid backdrop of this demi-monde, Theo Aronson presents the first full account of the curious life of Queen Victoria Nina Auerbach , New York

The Cleveland Street London

The Cleveland Street

HISTORICAL NOTES: In 1889, the year in which this scandal takes place, it is legal for girls aged 12 and boys aged 14 to marry (with parental consent). Most people started work at the age of 6 (or younger) to help support their families and men had a life expectancy of just 40-45 years of age. Male homosexuality was illegal and punishable, if convicted of buggery, to penal servitude for life or for any term of not less than ten years. The death penalty for buggery had only recently been abolished in 1861.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century a gentleman by the name of Charles Hammond ran a male brothel located at No 19 Cleveland Street in London Oxford Street

This all changed on 4th July 1889 when a telegraph boy called Charles Swinscow was searched as part of an ongoing investigation into money theft at his employers, the General Post Office. Eighteen shillings were found in his pockets, which at the time was worth more than a weeks salary to such a young man. Swinscow was taken in for questioning as part of the police operation.

When asked how he came to have such a large sum of money in his possession, Swinscow panicked and confessed he'd been recruited by Charles Hammond to work at a house in Cleveland Street where, for the sum of four shillings, he would permit the brothel's clients to "have a go between my legs" and "put their persons into me".

He then identified a number of other young telegraph boys who were also renting themselves out in this manner at the Cleveland Street

Who Was Involved:

Henry Horace Newlove 16 yrs Telegraph Boy - GPO 'Recruiter' for Hammond

Charles Thomas Swinscow 15 yrs Telegraph Boy - First boy arrested for 'theft'

George Alma

Charles Ernest Thickbroom 17 yrs Telegraph Boy

William Meech Perkins 16 yrs Telegraph Boy - ID's Lord Alfred Somerset as a 'client'

Algernon Edward Allies 19 yrs Houseboy - The Marlborough Club, used by Lord Somerset

George Barber 17 yrs George Veck's 'Private Secretary' and boyfriend

John Saul 37 yrs Infamous London rent boy - Possibly aka Jack Saul

Charles Hammond 35 yrs Brothel keeper of 19 Cleveland Street , London

George Daniel Veck

aka Rev George Veck

aka Rev George Barber

40 yrs Ex General Post Office (GPO) employee, sacked for indecency with Telegraph boys. Lives at 19 Cleveland Street Gravesend , Kent

PC Luke Hanks Police officer attached to the General Post Office

Mr Phillips Snr postal official who questions Swinscow with Hanks

Mr C H Raikes The Postmaster General

Mr James Monro Metropolitan Police Commissioner

Frederick Abberline 46 yrs Police Chief Inspector, infamous for the 'Jack the Ripper' investigations in 1888, London

PC Richard Sladden Police officer who carried out observations on the Cleveland Street

Arthur Newton Lord Arthur Somerset's solicitor. Later to defend Oscar Wilde at his trial in 1895 and notorious murderer Dr Crippen

Prince Albert Victor, the Duke of Clarence 25 yrs Rumoured to be a 'Brothel Client' - Went on a seven month tour of British India in Sept 1889 to avoid the press & trials

Colonel Jervois of the

2nd Life Guards

'Brothel Client' - Winchester

Lord Arthur Somerset

aka Mr Brown 37 yrs 'Brothel Client' - Named in Allies letters as 'Mr Brown'

Henry James Fitzroy

39 yrs Accused of being a 'Brothel Client' - Earl of Euston

Sir Augustus Stephenson Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP)

Hon Hamilton Cuffe Assistant DPP - Six years later he would prosecute Oscar Wilde at his trial in 1895 as the Director of Public Prosecutions

Ernest Parke Journalist - North London Press

After The Arrests

The officer in charge of the case, Chief Inspector Frederick Abberline, procured a warrant to arrest Charles Hammond on a charge of conspiracy to "to commit the abominable crime of buggery", but when he went to Cleveland Street Hammond

The police made arrangements to observe the comings and goings at No 19 Cleveland Street, noting that a 'Mr Brown' called there on the 9th and 13th July 1889, following which on the 25th July both Swinscow and Thickbroom identified Mr Brown as one of the their clients.

Mr Brown was followed by police back to army barracks in Knightsbridge where he was soon identified as Lord Arthur Somerset, a younger son of Henry Charles Somerset, 8th Duke of Beaufort, a Major in the Royal Horse Guards and equerry to Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII.

Papers were sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions with a view to prosecuting Lord Arthur on a charge of gross indecency. The Prince of Wales was incredulous when he heard of it

"I won't believe it, any more than I should if they accused the Archbishop of Canterbury" he said.

Despite this gesture of support, Lord Somerset placed the matter in the hands of his solicitor Arthur Newton who contacted the DPP simply to mention the fact that his client, if prosecuted, might well name the Duke of Clarence whilst he was giving evidence in court.

Given that Albert, Duke of Clarence was the eldest son of the Prince of Wales and second in line to the throne, it was clear that the government would not want his name associated with the homosexual brothel at Cleveland Street Boulogne , France

But whilst Somerset

This might have been the end of the story had it not been for a journalist named Ernest Parke, who ran a story on 28th September 1889 in the 'North London Press', claiming that the "heir to a duke and the younger son of a duke" had frequented Cleveland Street.

Again, on the 16th November he went so far as to name both Arthur Somerset and Henry James Fitzroy, the Earl of Euston, as the men in question and dropped a broad hint to his readers, by referring to a gentleman "more distinguished and more highly placed", that a member of the royal family was also involved.

Ernest Parke believed that it was safe to name the two young aristocrats as they had both fled the country. He was correct as far as Lord Arthur Somerset was concerned, but the Earl of Euston was not, as he thought, in Peru, but rather in England, and thus in order to defend his reputation felt obliged to bring a charge for criminal libel against Edward Parke.

The trial was heard at the Old Bailey on the 19th January 1890. Whilst Henry Fitzroy admitted that he had been to 19 Cleveland Street

Ernest Parke however produced a witness named John Saul, who went into some detail describing the kind of services that he had provided for Henry Fitzroy at Cleveland Street

One more trial was to arise as a result of the Cleveland Street Somerset Newton was brought before the court on the 12th December 1889 and charged with conspiracy to pervert the course of justice for allegedly interfering with witnesses and arranging their disappearance to France

He was convicted but received the relatively mild punishment of six weeks in prison. He was even allowed to resume his legal practice afterwards and was later to become better known for representing the author and playwright Oscar Wilde.

This was still not quite the end of the matter as the MP Henry Labouchère, a noted campaigner against 'homosexual vice', who had earlier been responsible for including the offence of 'gross indecency' within the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, became convinced that some kind of 'cover-up' had been launched by the authorities.

On the 28th February 1890 he tried to persuade Parliament to establish a committee to investigate the whole affair, but his motion was defeated by a vote of 204 to 66. Henry felt so strongly on the matter that he became over animated during the debate on his motion and he was suspended from Parliament for a week.

Finally...

Thus the Cleveland Street Scandal passed into history and ceased to be a matter of contemporary significance, however, from evidence that has since become available, it now appears that the Duke of Clarence was indeed a likely client of the Cleveland Street

I grateful acknowledge the following works used in my research:

The Cleveland Street

The Cleveland Street Montgomery

Inside story: 19 Cleveland Street

Officially, this house no longer exists, thanks to an 'indescribably loathsome scandal'. But Matthew Gwyther finds life goes on there

By Matthew Gwyther12:00AM BST 21 Oct 2000 / http://www.telegraph.co.uk/property/4811529/Inside-story-19-Cleveland-Street.html

IF you wander up and down Cleveland Street London England

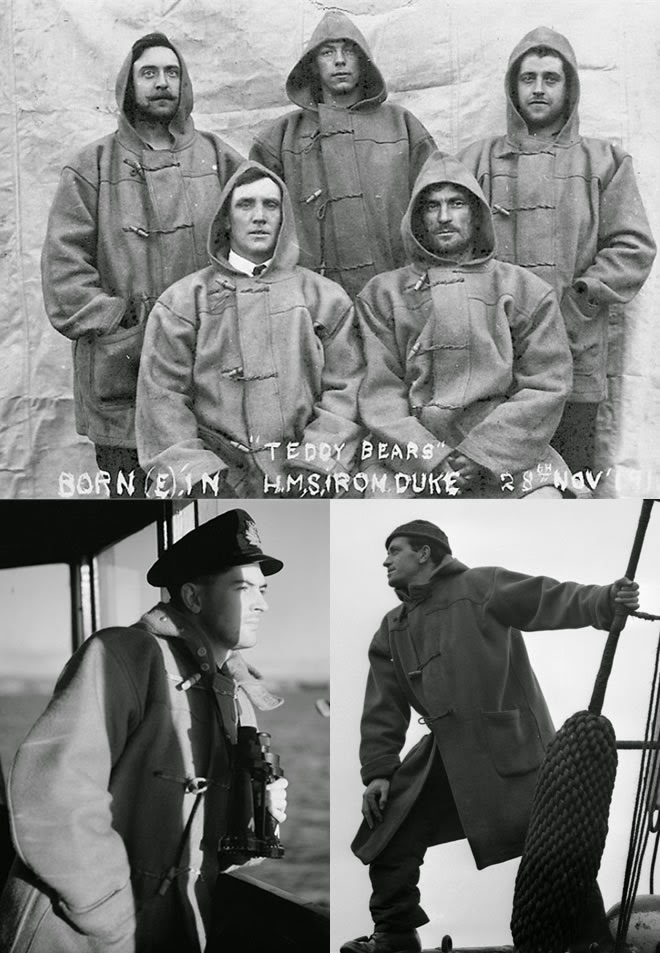

"Den of infamy": Lord Arthur Somerset, at the heart of the Fitzrovia based scandal

The "indescribably loathsome scandal", as one newspaper called it, began in the late summer of 1889 when PC 718, Luke Hanks of the General Post Office's own police force, stopped and interviewed a 15-year-old telegraph boy called Charles Swinscow, who worked at St Martin 's Le Grand and who had been found carrying 18 shillings. This was the equivalent of two months' wages, and he was immediately accused of stealing.

Swinscow protested that he had earned the money by "going to bed with gentlemen" at the rate of four shillings a time at Number 19. He revealed that several other telegraph boys did the same thing to supplement their wages.

Scotland Yard put the house under watch and confirmed that "a number of men of superior bearing and apparently good position" were frequent visitors. When they finally raided Number 19, the owner, Charles Hammond, had already fled to France Hammond

Some of the men calling at the house were, indeed, of good position, and when word got out of their identity, the scandal began. They were said to include Lord Arthur Somerset, son of the Duke of Beaufort, the Earl of Euston and a Colonel Jervoise from Winchester

Although his name was never mentioned in the British press, the American and French newspapers discussed his alleged involvement quite openly. The affair was to cause the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, no end of embarrassment.

The evidence against Lord Arthur was strong. The police had letters to him from one of the prostitutes and several statements from other boys. He was allowed to escape to Vienna France

The events at the "den of infamy", as the Illustrated Police News termed the establishment in Cleveland Street

At the first trial, Henry Newlove and George Veck (who had tried to escape dressed as a vicar) were found guilty of procurement but received light sentences of less than a year. (Within a decade, Oscar Wilde was to be sentenced to two years' hard labour for similar offences.)

During the second trial, Euston claimed in the box that he had attended the house in the belief that he was going to watch heterosexual poses plastiques, or the Victorian version of a strip show. Despite some compelling evidence in his favour, Parke received 12 months in jail, which the Victorian writer Frank Harris described as "infamous and vindictive". Prince Eddy was sent off to India

The renumbered house is now divided into three flats, and Flat Two - where the bedrooms used to be - is owned by a German chef, Michael von Hruschka. He is the boss at The Birdcage in nearby Whitfield Street London

Unfortunately, Mr von Hruschka has injured his back and finds it nearly impossible to stand for long periods at his stove. So his two-bedroom flat is now for sale. It is fairly small, the kitchen is contained in an alcove off the living room and the carpets need a clean, but the asking price for this blue plaque-free piece of history is a cool £280,000 - about double its value two years ago. Such prices are not uncommon for Noho (north of Soho) or Fitzrovia, which has been hailed as "the new Docklands" by some, although the view from this section of Cleveland Street University College Hospital

Mr von Hruschka's business partner, Caroline Faulkner, from whom he bought the place, acknowledges that the area is a "very-on-the-edge sort of place. It's still a bit seedy". But as an added incentive, the purchaser will get a free meal for two at The Birdcage.

The flat can be viewed through Foxtons in Mayfair on 020 7973 2000.